Tag: computational-design

-

PlumaDesign, 2020

PlumaDesign, 2020With a design framework applicable to any site in the world, the Pluma installation envisions a lightweight future where structures generate more energy than they embody. Earned honorable mention at the IASS 2020 Design Competition.

Pluma demonstrates how form can follow function across disciplines and performance metrics. The design features photovoltaic membranes suspended in a lightweight cable system, resembling a flock of birds in flight.

The shape and orientation of the membrane ensemble is precisely tuned by an optimization algorithm to maximize solar radiation exposure and power generation on the site in Surrey.

Its supporting frame consists of standard timber elements assembled into cruciform sections, with simple, repeated connection details that are cost-effective. The foundation is a concrete slab hollowed out with compressed sawdust blocks as lost formwork, reducing the embodied energy compared to a typical slab by half.

-

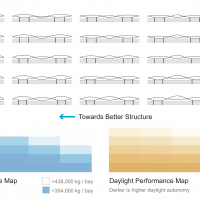

A Platform of Design Strategies for the Optimization of Concrete Floor Systems in IndiaMohamed Ismail and Caitlin Mueller, International Conference on Structures and Architecture, 2019

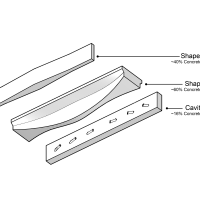

A Platform of Design Strategies for the Optimization of Concrete Floor Systems in IndiaMohamed Ismail and Caitlin Mueller, International Conference on Structures and Architecture, 2019This paper presents a developing platform of design strategies for concrete construction in India. More specifically, this paper will discuss three strategies for the design of horizontal spanning concrete elements. Each strategy involves a different method of structural optimization with varying performance levels based on material reduction and structural capacity. Designed for India’s affordable housing construction, the elements are constrained by the fabrication methods and materials available to India’s construction industry, merging structural design with the development of affordable housing technology. Material savings range from 16% to 50% depending on the strategy. The strategies are used to design, fabricate, and structurally test prototypes, exploring their potential for India’s construction needs.

-

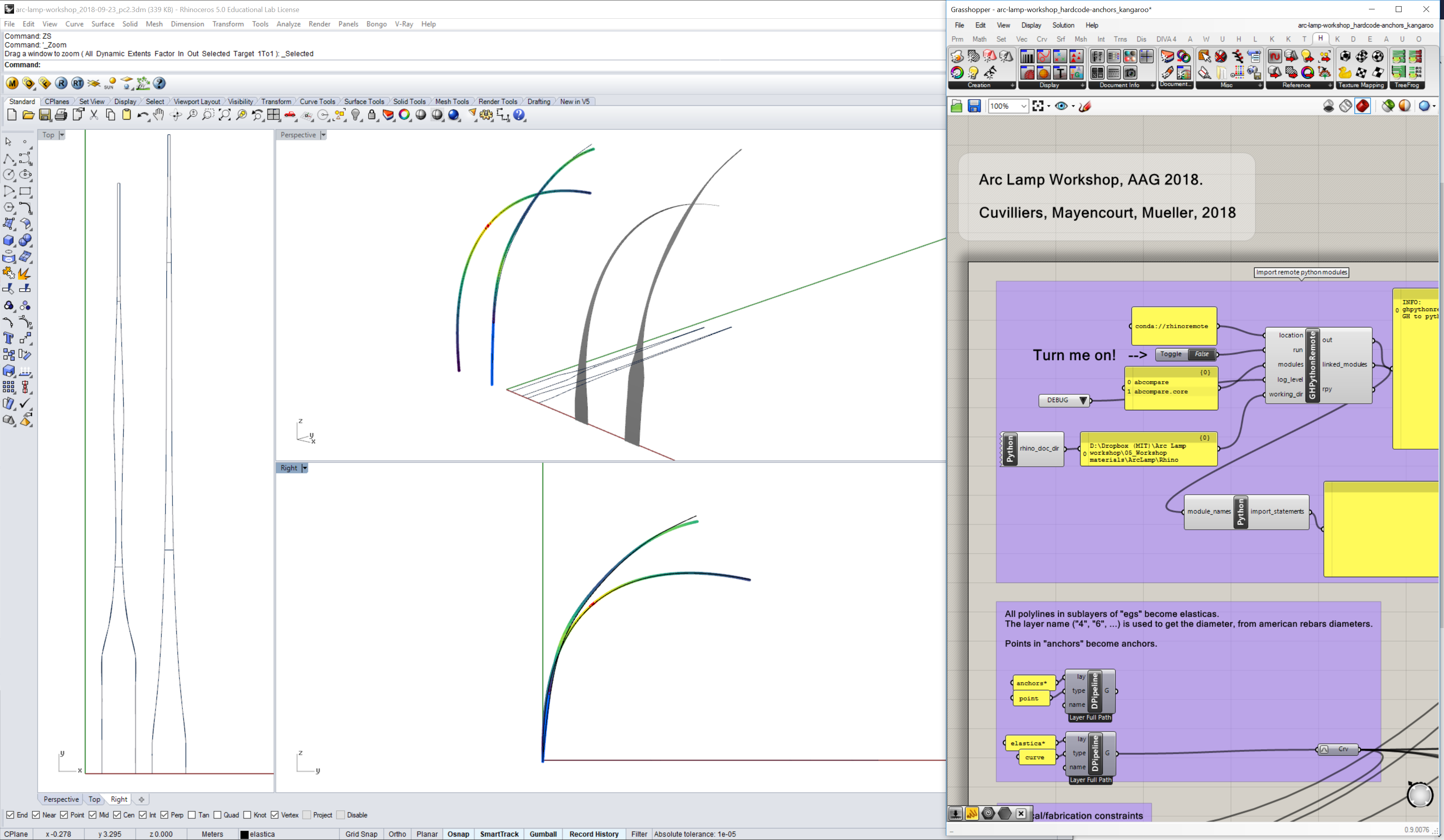

The Arc Lamp workshop at AAG 2018: active bending and digital fabrication

The Arc Lamp workshop at AAG 2018: active bending and digital fabricationDigital Structures' Caitlin Mueller, Paul Mayencourt and Pierre Cuvilliers were in Gothenburg, Sweden this September 2018, teaching a workshop on active bending at the Advances in Architectural Geometry conference hosted at Chalmers University. In this workshop, we explored the design of bending-active structures with variable cross-sections to fit a target design shape. Over the two days, the participants used computational form-finding tools for bending-active structures, and each designed and built an arc lamp. The participants learned state-of-the-art methods for simulating bending-active behavior and for the control and optimization of their equilibrium shapes. These methods could be applied to the design of large-scale bending-active structures such as elastic gridshells.

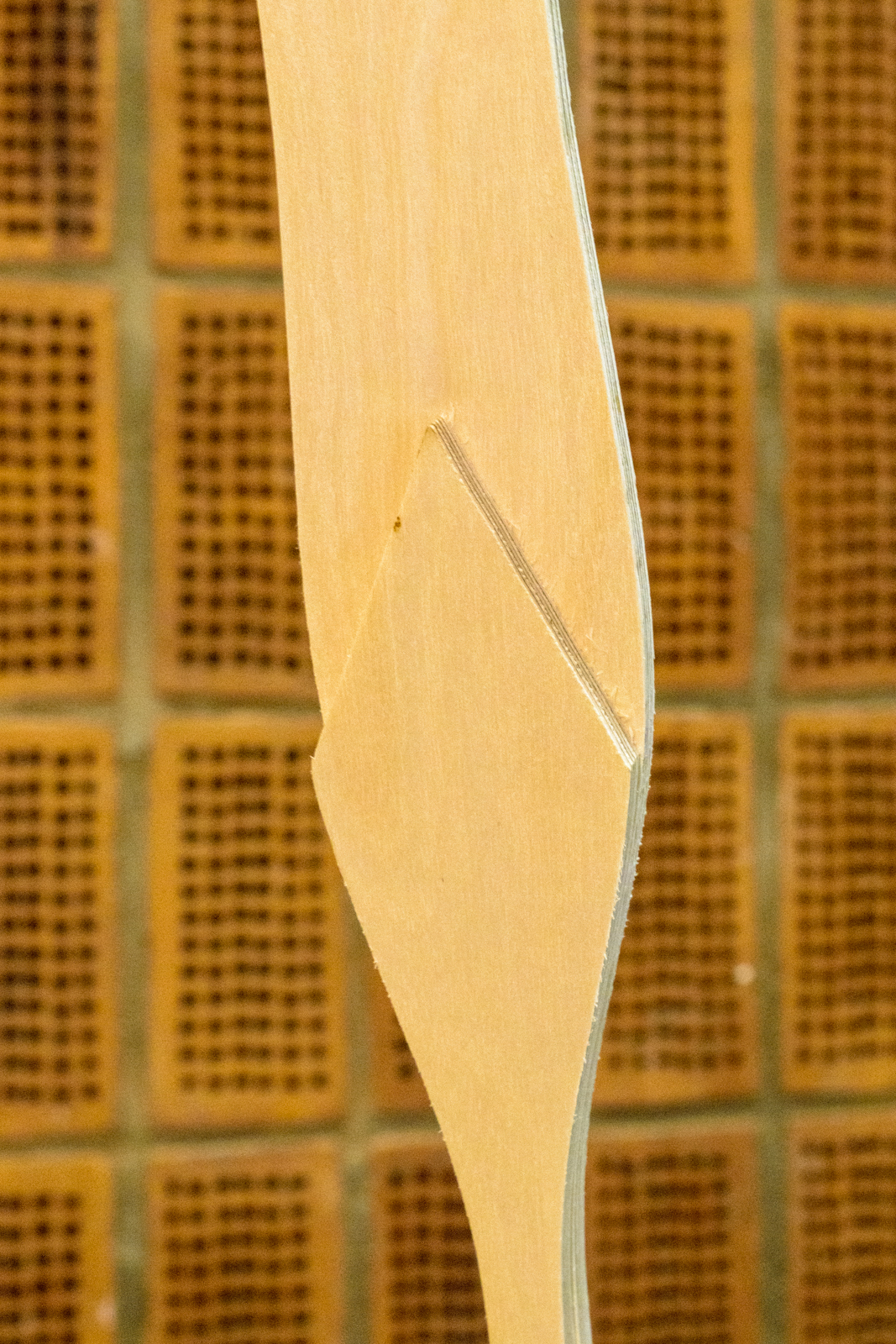

After a short introductory lecture on active bending structures, the workshop immediately got very practical, with the participants testing the plywood we would use to build the lamps, determining stiffness and resistance. With these values on hand, it was time to start trying out the design workflow on small-scale prototypes. Small teams formed, first design ideas emerged, and we started comparing the designs against their simulated shapes and against each other. The prototypes were laser-cut sheets of plywood, with rudimentary attachments; this made iterating on designs a lot easier.

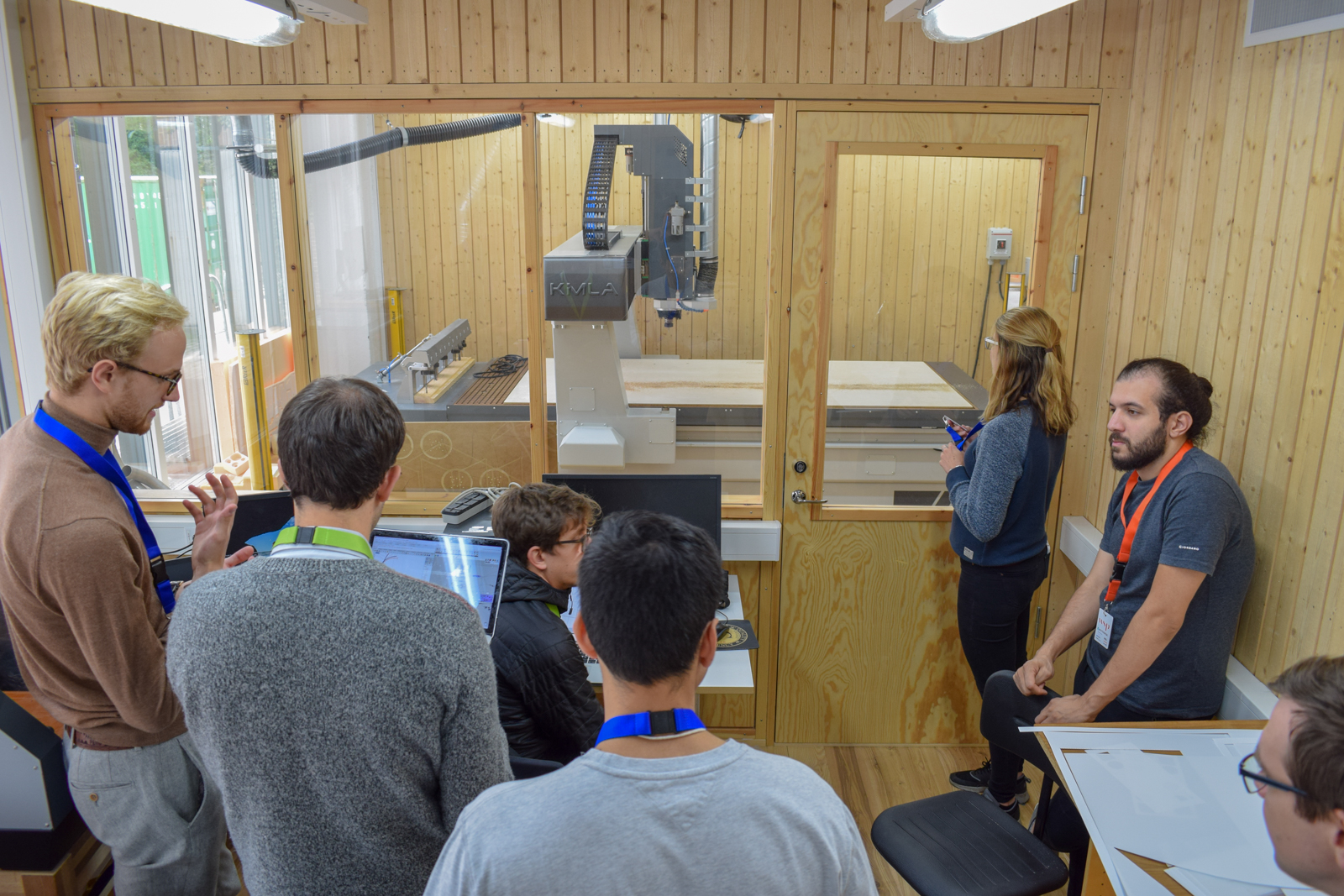

This prototyping stage gave everyone a better sense of the design space we were exploring, and let us start exploring the limits of the software tools. For the next step, we designed lamps at a much larger scale: 2-to-4-meter strips of plywood, from 4-mm- and 6-mm-thick sheets. After finalizing the designs, it was time to start up the CNC router.

As soon as the cuts were ready, it was assembly time. We fabricated bases for the lamps in the beautiful wood workshop of Chalmers University, then moved to the conference space where the lamps would stay on display for 3 days.

Most lamps found their spot next to another bending-active structure, a wooden pavillion designed by Alexander Sehlström.

The rest was spread around the conference space, and all were very intriguing.

Some construction details:

All the lamps we built:

Overall, a great workshop. We all learned a lot in these two days!

-

Integrated design for greenhouse in Portola ValleyDesign, 2018 - Present

Integrated design for greenhouse in Portola ValleyDesign, 2018 - PresentThis ongoing design project looks at an "eco-modernist" custom greenhouse to be built in Portola Valley, California. The objective of this greenhouse is to meet requirements for extended-season plant growth while requiring limited intervention for operation and applying approaches of structural efficiency. Tools such as our Design Space Explorer suite are used to explore and select among a wide design space that meet performance objectives to varying degrees. Local materials and custom structural joinery will be used in the greenhouse construction.

-

Design variable analysis and generation for performance-based parametric modelling in architectureNathan Brown and Caitlin Mueller, International Journal of Architectural Computing, 2018 (In press)

Design variable analysis and generation for performance-based parametric modelling in architectureNathan Brown and Caitlin Mueller, International Journal of Architectural Computing, 2018 (In press)Many architectural designers recognize the potential of parametric models as a worthwhile approach to performance-driven design. A variety of performance simulations are now possible within computational design environments, and the framework of design space exploration allows users to generate and navigate various possibilities while considering both qualitative and quantitative feedback. At the same time, it can be difficult to formulate a parametric design space in a way that leads to compelling solutions and does not limit flexibility. This paper proposes and tests the extension of machine learning and data analysis techniques to early problem setup in order to interrogate, modify, relate, transform, and automatically generate design variables for architectural investigations. Through analysis of two case studies involving structure and daylight, this paper demonstrates initial workflows for determining variable importance, finding overall control sliders that relate directly to performance, and automatically generating meaningful variables for specific typologies.

-

“Always question your own preconceptions”: Discussing the future of technology in architecture with Martha Tsigkari of Foster + Partners2018-02-15, Author: Demi Fang

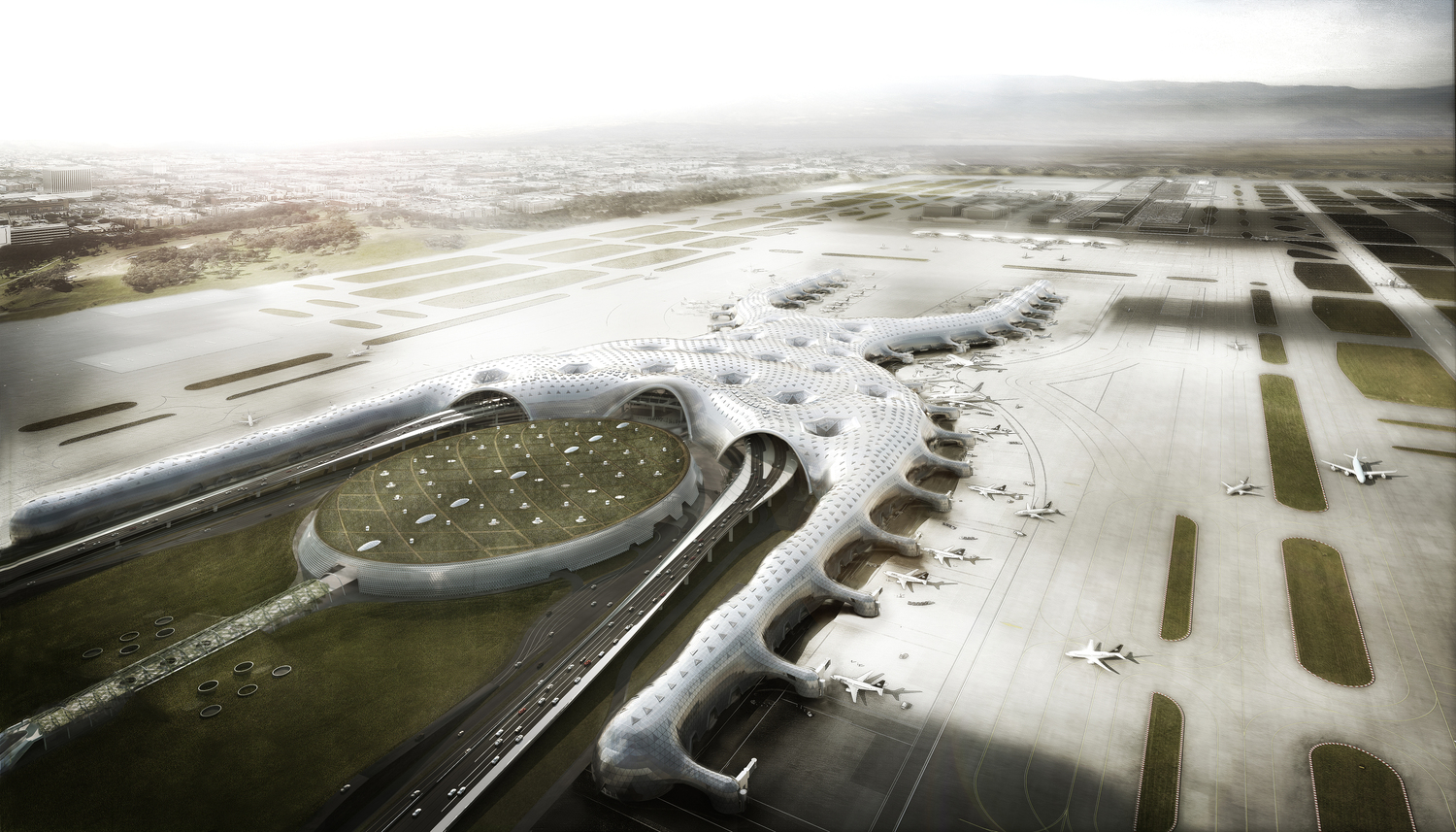

“Always question your own preconceptions”: Discussing the future of technology in architecture with Martha Tsigkari of Foster + Partners2018-02-15, Author: Demi FangAmidst the excitement of ACADIA 2017 on MIT’s campus, we found an opportunity to sit down and chat with Martha Tsigkari, who presented the New International Airport Mexico City (2020) with her colleagues. Tsigkari trained as an architect-engineer in Greece before obtaining a master’s degree at The Bartlett’s Architectural Computation programme at UCL, which she describes as “a computer science course for designers and architects.” She has been at the Applied Research + Development (AR+D) group at Foster + Partners’ London office ever since. In this post, we synthesize some of her thoughts on the future of technology in architecture, on the art of collaborating across disciplines, and on the humility necessary for innovation. Quotes have been edited for clarity.

The main focus of Tsigkari’s role and presentation of Foster + Partners’ highly anticipated New International Airport Mexico City was “evidence in performance-driven design. It’s all about how all the analysis and optimization can be incorporated through the life of the model to make for a better solution,” Tsigkari says.

On working with Arup, the engineers on the airport project, Tsigkari says that “it was a fantastic collaboration. The design process was not conventional in that we knew how we wanted the space frame to look aesthetically, so we developed all the processes necessary to create a structurally viable and well-performing space frame. Arup was confident in the processes we had and fully adapted our topology. They would receive our permutations of the final model, analyze them, and return with the sizes of the nodes and elements required. From that feedback we would make some aesthetic decisions; if we saw some really big nodes, for example, we knew that we had to do something with the topology and the smoothing of the space frame at that location.”

New International Airport Mexico City. Copyright Foster + Partners

New International Airport Mexico City. Copyright Foster + PartnersAside from performance-based design, the AR+D group at Foster + Partners focuses on multi-faceted and cutting-edge topics. “We see a huge future within architecture in Virtual Reality (VR),” Tsigkari says. “We also do a lot with simulations and optimization; we have written our own simulation engines that run tens or hundreds of times faster than those in the industry. I worked a lot with interoperability - making sure that this simulation works with all the different platforms that we’re using and that they talk with each other. We’re using those tools through optimization processes, whether it’s cognitive computing or genetic algorithms.

“We are also quite heavily involved with innovative interfaces to help designers understand the repercussions of their decisions very early on in the design process,” says Tsigkari. “We’re doing a lot of things with innovative materials and design-to-fabrication processes as well as looking into interesting things like the Internet of Things, seeing how we can make smarter buildings and cities that not only get constant feedback from the experiences that people have, but also better themselves without human input.

Tsigkari emphasizes the significance of nonlinear analyses and adaptive processes in future steps to improve the built environment. “There is a fundamental problem in the way we design most of our buildings: typically, it is a linear analysis for a specific pseudo-optimal state. For example, we design buildings based on the worst-case scenario of an earthquake. The resulting design is going to be useless for 90% of the time - it is only useful for the one-off chance that an earthquake happens. On the other hand, if you see how nature works, and if you embrace the idea of compliant mechanisms and nonlinear analysis, then you start embracing the ideas of embodied computation that Axel Kilian was explores in his tower, where you don’t optimize based on worst-case scenarios but instead try to design a form intelligent enough to optimize itself based on the feedback it gets and based on a specific state it always needs to return to. For me, this idea is extremely crucial. It feels like a natural next step in how we build.”

Tsigkari goes on to describe an ongoing research collaboration with Autodesk’s Panos Michalatos, Matt Jezyk and Amira Abdel-Rahmani: “We are essentially running nonlinear analyses for compliant mechanisms on the material level. More specifically, we are working with thermally actuated laminates. You can see situations where a facade is no longer a static element, but is externally actuated and adapts.

“A big part of our research right now is to understand the laminate layering required for the desired adaptations. My colleague Marcin Kosicki has been working with TensorFlow to develop a neural network, feeding in different laminates and the associated disfiguration of the material.”

Tsigkari maintains a humble, if not borderline cynical, perspective on the state of technology in architecture today. “Architecture as a profession is, I daresay, backward-looking. The industry is we are very slow to adapt to new technologies. It’s interesting to see that in the past decade, there has been a significant shift towards more computational design processes. I think what made the shift is the development of tools - for example, Grasshopper for Rhino - which made visual scripting quite intuitive. It introduced a different interface for users towards computer-science-based processes.”

How does Tsigkari train students towards such a rapidly evolving field? “What I learned at The Bartlett was not a particular software but computer science and algorithms: how to write a vanilla AI algorithm and how to potentially apply this to design problems. The trick is to get the underlying knowledge of what these processes are and how they could be used. You can use that knowledge in whatever software you want as long as you know what it is, how it works, and what you can expect from it.

“If what we see in Grasshopper is the skin of computational design, what we’re teaching is the bones and muscles of it; the underlying principles of computation. We are teaching algorithms that are not new - other fields have been using these for the past 60 years. In architecture we have started using them in the past decade. The reality is that we’re 60 years behind industries like rocket science, the chemical industries, or the army. It’s interesting to see how people feel extremely proud of using tools that have been around for over half a century and have been successfully used in many other industries with quite innovative outcomes.”

The interdisciplinary nature of the AR+D team helps. “We have people who have architectural backgrounds or engineering backgrounds, or both, but we also have artists, computer scientists, aeronautical engineers... I think that looking at what is achieved in other industries is absolutely key to being able to innovate within our own industry in terms of building processes, materials, and even techniques. Only now are we starting to look at how swarm robotics can affect buildings; techniques like these have been used extensively in other industries in the past with fantastic results. This kind of cross-referencing that can be beneficial for our industry.”

Martha Tsigkari with Francis Aish and Norman Foster at the keynote of Architectural Advances in Geometry Symposium 2016. Image courtesy of AAG 2016

Martha Tsigkari with Francis Aish and Norman Foster at the keynote of Architectural Advances in Geometry Symposium 2016. Image courtesy of AAG 2016It is by chance that Tsigkari occupies an unusual career path at the intersection of practice and academia. “My involvement with teaching is really driven by my late mentor, Alasdair Turner. He initiated the master’s programme I’m teaching at now, and he was this fantastic personality - a computer scientist, who had a lot of interest in tying computer science, architecture, and philosophy together.

“Alasdair took me from a world where I was unsure where I wanted to be and led me down a rabbit-hole to a completely different world of possibilities. After his untimely death, I kind of took over his lectures on genetic programming. For me, teaching is about extending his legacy to the newer generations, helping people the same way I was helped, to understand the art of the possible. So that’s how I ended up in academia.

“I actually find it extremely hard to be both in academia and in industry because they’re both very time-consuming. You need to be very strict with your time,” says Tsigkari. “Having said that, it gives fantastic opportunities to educate newer generations with notions you have in industry. I do not simply show my students an algorithm, but I can also show them its potential by showing them the projects I’ve used it on. It gives people a direct connection between the algorithm (which is quite abstract) and what can be done with it (which is quite tangible). I find that this connection is really interesting, and it’s very interesting for the students as well. I’ve always gotten very positive feedback about having that understanding.

Asked to give advice to students aspiring to be architects or engineers, Tsigkari pauses and admits, “This is a very difficult question. I’m horrible at giving advice; I feel that people should be their own advisers and they should do what feels right for them.”

Despite these comments, Tsigkari gradually offers some striking pieces of advice as she continues. “I think you should always do what feels right for you, and that you should always question everything. I would say you should also always question your own preconceptions of what things are. So if you are on the verge between architecture and engineering, question what these two mean for you. Your preconceptions are going to lead you down one road that may not be what you think it was. Step back; don’t make big plans. Feel your way through things that you’re interested in, and something will always come up.”

Citing her own experience, Tsigkari recalls that “as with everything in my life, I had no plans. I never saw myself in a certain position, ever. Other people had plans for me, which I had never followed. I went to a very traditional school, and I learned a lot, but they were not things I wanted to to do for the rest of my life. I mutated, diversified, and changed myself in order to pursue what I wanted.”

Tsigkari continues, “If I were to advise something, it would be to not tag yourself. Do not call yourself an architect or an engineer or a computer scientist - nowadays, I think the da Vincian perception of a person is what is closer to what we need in order to innovate. It is important to understand various disciplines while always saying to yourself that you know very, very little. That will always drive you to become better. It will take the danger out of what you do and will make a better person out of you.

“I look back at my university years with a sense of newfound introspection. Had I known then what I know now, I would never have chosen architecture - never. I would possibly go into artificial intelligence, robotics, or neuroscience, and do something completely different, because I see even now that these are the things that are interesting to me.”

Reflecting briefly on the direction in which she hopes to steer her future, Tsigkari continues, “I guess that I am trying to shift my path towards those topics that I am interested in. It becomes more difficult as time goes by and you get more responsibility at work, but, you know... I don’t think it’s ever too late.”

-

Design, mechanics, and optimization of interlocking wood jointsResearch, 2017 - Present

Design, mechanics, and optimization of interlocking wood jointsResearch, 2017 - PresentDespite the longstanding craft of interlocking wood joints in North American and East Asian carpentry, modern timber structures frequently use metal connectors in mid-rise construction. This research explores the structural capabilities of interlocking joints between beams and columns for mid-rise timber frame construction. Research methods include parametric design, structural modelling, digital fabrication, and experimental load testing.

-

Computational tools and experimental making in timber construction: In conversation with Christopher Robeller2017-11-03, Authors: Demi Fang Paul Mayencourt

Computational tools and experimental making in timber construction: In conversation with Christopher Robeller2017-11-03, Authors: Demi Fang Paul MayencourtOf the many exciting innovations in digital fabrication permeating architecture research today, the work of Christopher Robeller stands out in the growing field of timber construction. Robeller completed his PhD in 2015 on the integral mechanical attachment of timber panels at Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL)’s laboratory for timber construction, IBOIS. He spent the following two years as a post-doctoral researcher at the Swiss National Centre in Research (NCCR), applying his research to the construction of a fully functioning building: the Vidy Theatre. Recently appointed Junior Professor in Digital Timber Construction at TU Kaiserslautern, Robeller presented his process and experience working on the Vidy at the ACADIA 2017 conference at MIT in early November of this year.

Robeller also stopped by to chat with us about his work and his thoughts on wood, the built environment, and the importance of experimentation in making. The questions and responses below have been edited for clarity.

Digital Structures: How did you get to be interested in and involved with wood?

Christopher Robeller: My family has been working with timber for a couple of generations, but for more pragmatic things like making windows. My fascination from childhood was always that wood was a nice material to work with - it’s not too dirty, and it’s something you can craft. It’s even got a nice smell to it! It’s a material I’m very passionate about.

DS: Can you describe your training in architecture and/or engineering?

CR: I studied architecture at the London Metropolitan University. It was not a mixed course, but I was always very interested in engineering at the same time. I was very impressed by all of the creativity and ideas being generated in architecture school, but there was a point where I realized that in order to make it really work, you have to overcome a lot of engineering challenges, and only if you really manage that can you make really great architecture.

I have combined my interests in architecture and engineering in the last few years. I first worked with Achim Menges, through which I collaborated a bit with Jan Knippers’s laboratory, a team of mostly engineers. When I went to IBOIS at EPFL for my PhD, I found that I was one of the few architects - there were times when I was one of two architects on a ten-person team.

It would be a shame for a building to have a strong and interesting architectural concept but have details that don’t match the quality of the rest of the building. I found an opportunity through the PhD to focus on those more in-depth aspects of geometry, fabrication, and engineering.

DS: What are your thoughts on relationship between architecture and engineering?

CR: In my traditional experience in architecture, there is not much interaction. You expect the engineer to figure it out, and most projects rely on the state-of-the-art. Architects and engineers get to work much more closely together in more experimental projects in academia.

Computational tools offer a chance for architects and engineers to work together. These tools offer control over design, and that control is valuable in both fields. There is only so much you can do with a software that comes off the shelf that was developed for certain purpose; if you want to use the software for a different purpose, you have to modify the software to make it do what you want it to do. Architects and engineers are starting to take advantage of this.

This area is where the two fields reach a bit of a common language. I am seeing computer scientists, civil engineers, and architects work on similar collaborative models. You might find a very interesting solution for your architectural or engineering problem in some algorithm that has just been developed by some computer scientists. Then you can get together and plug in together if you’re working on a common ground such as a common programming language.

DS: What are your thoughts on the relationship between academia and practice?

CR: They can be worlds apart, especially in timber construction. The community of timber construction is highly skilled but can sometimes be rather conservative. On the other hand, there is the creative and artistic community of architects who design amazing things with timber. It’s really interesting how you have to find a balance between these two groups because they can be very far from each other.

Given the complexity of wood, you have to bring the two groups together. You have to talk to the companies in the construction industry that specialize in timber. In design and engineering, we are usually generalists working with many materials, whereas these companies have long ago specialized in one material and have gained a lot of knowledge over the decades. That’s something that should be respected. If you get in touch with them - which you only do through these experimental projects - you learn a lot from them.

There is a lot of discussion right now over the social component of digitalization. There is a danger of neglecting people who are not in the loop. Once again, computational tools allow you to integrate people in industry into the design process. I think we’ve done that with the Vidy Theatre: we went to companies, talked to the experts there, and included them in the process. I specifically developed a program that the fabricator there could use. We didn’t use software that eliminate the engineer and the fabricator from the design and manufacturing process. It’s something we should think about: how these digital workflows can incorporate specialists.

DS: Do you hope to continue bridging these fields - architecture and engineering, and research and practice - through your new professorship?

CR: I am definitely trying to bring the four worlds together. People in practice already know how to do things; they’re absolute professionals in the state-of-the-art. In teaching, the beauty is in not having that expertise yet. This lets you think about things in a completely different way, in a free and open way, and you might come up with interesting and intuitive solutions.

For example, I was making the first prototype for a timber plate shell construction project in the workshop by myself, with my hands. I was assembling the prototype on its side because intuitively it made sense to allow the weight of the elements to help with insertion. But in building design, it was being designed right-side-up as usual, and that was what was causing all the problems when we tried to put together a larger prototype. It wasn’t until we finally thought back to the first prototype that I built sideways that we realized what the problem was. I might not have had that experience if I hadn’t made that prototype myself.

Timber plate shell prototype assembled on its side. Image courtesy of Christopher Robeller.

Great architects and engineers are people who quite often have been working physically themselves making things, making prototypes and models. This very rarely happens in actual architecture-engineering design processes - it’s only in academia that a designer of a building actually goes and makes not only a representational model but a functional model of some joint or assembly - himself.

Robeller (left) chats with DS students Courtney Stephen (middle) and Paul Mayencourt (right).

DS: What is something that excites you the most about future possibilities in wood?

CR: We can do amazing things with timber in fabrication, and I think that’s the biggest development in the last ten, twenty years. If you had shown me our work on the Vidy Theatre ten years ago, I would have thought it was magic. Now having done all of it, it doesn’t really seem like magic anymore.

We have come a far way, and it’s much easier to do these things now. While geometry processing and fabrication have become more manageable, the building implementations allow us to focus on new challenges such as integrated concepts for structural engineering and building physics.

One reason I went to IBOIS is because of their machinery (5-axis CNC machine). If you want to experiment with the making of today, you need the technology to be accessible; you don’t have that everywhere. In educational institutions, it’s very important to not only have the technology but to have it accessible to the greater community.

It’s funny, I talked to companies like Blumer Lehmann - they had their first 5-axis machine in 1985. That’s how long they’ve had it! Mechanically, not much has changed. You probably could have done the Vidy Theatre back then. The computer was surely capable enough. The limitation was accessibility: you didn’t have the CNC machinery in universities, at least in architecture and engineering. CNC technology may have been developed at MIT, but it took a long time for it to come into architecture and building in a way that’s accessible to the architecture research community.

Construction of Vidy Theatre. Image courtesy of Christopher Robeller.

Another exciting challenge I see is that not only do we have something very beautiful, but we also have something that can make a positive impact in terms of the ecological construction that we need so much. It’s like having your cake and eating it too! We have something beautiful, something interesting, we can address the challenges of digitalization by making jobs more pleasant and more interesting and less hard manual work, and at the same time we can maybe make it more ecologic. But that’s really a maybe; I’m very self-critical about my work so far, and it has not been something focusing on sustainability - yet. But this is clearly something I see as a realistic possibility and something I want to look more into.

DS: Do you have any advice for young researchers and architects who are interested in exploring and applying timber innovations?

CR: Be passionate and be creative. When you first begin as a student, you’re very free from any state-of-the-art that tells you how things are supposed to work. You have to use the moment. Eventually, of course, you have to learn all of the things, but every stage of the journey is an interesting step.

-

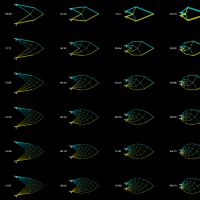

Computational Structural Optimization and Digital Fabrication of Timber BeamsPaul Mayencourt, Joaquin S. Giraldo, Eric Wong, and Caitlin Mueller, Proceedings of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) Symposium, 2017

Computational Structural Optimization and Digital Fabrication of Timber BeamsPaul Mayencourt, Joaquin S. Giraldo, Eric Wong, and Caitlin Mueller, Proceedings of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) Symposium, 2017This paper focuses on optimizing beams made of solid timber sections through a CNC subtractive milling process. An optimization algorithm shapes beams and reduces the material quantities by up to 50% of their initial weight. A series of these beams are then fabricated and load tested, and their strength is compared to standard timber sections.

-

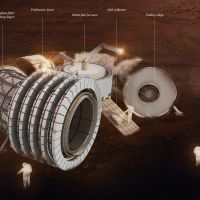

Structural challenges for space architecture: Engineering habitats for the Moon and MarsValentina Sumini and Caitlin Mueller, STRUCTURE Magazine, 2017 (In press)

Structural challenges for space architecture: Engineering habitats for the Moon and MarsValentina Sumini and Caitlin Mueller, STRUCTURE Magazine, 2017 (In press)Designing a structure on an extraterrestrial surface includes several challenges: the internal pressure; the dead loads/live loads under reduced gravity; the consideration of new failure modes such as those due to high-velocity micrometeoroid impacts; the relationships between severe Lunar/Martian temperature cycles and structural and material fatigue; the structural sensitivity to temperature differentials between different sections of the same component; the very extreme thermal variations and possibility of embrittlement of metals; the out-gassing for exposed steels and other effects of high vacuum on steel, alloys, and advanced materials; the factors of safety; the reliability (and risk) which must be major components for lunar structures as they are for significant Earth structures.

When considering a permanent settlement on another planet, one of the crucial aspect involves an evaluation of the total life cycle of the structure. That is, taking a system from conception through retirement and disposition or the recycling of the system and its components. Many factors affecting system life cannot be predicted due to the nature of the Lunar/Martian environment and the inability to realistically assess the system before it is built and utilized. Therefore, even if the challenges in space exploration are very peculiar, the colonization of satellites and planets could teach us to be wiser in our consumption of natural resources, pushing us to pursue efficiency and sustainability, here on Earth. The multidisciplinary methodology connected to space exploration research will be a wise starting point for optimizing the terrestrial consumption of natural resources for designing more sustainable architectures and improving ground logistics research.

-

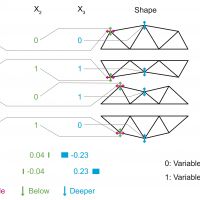

Automated performance-based design space simplification for parametric structural designNathan Brown and Caitlin Mueller, Proceedings of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) Symposium, 2017

Automated performance-based design space simplification for parametric structural designNathan Brown and Caitlin Mueller, Proceedings of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) Symposium, 2017As computation has advanced, more designers are becoming familiar with parametric and performance-based design space exploration, techniques that can provide feedback and guidance even in early-stage design. However, two downsides of such techniques are the time and expertise required for problem setup, and the potential of the large volume of generated data to become overwhelming and difficult to absorb. Researchers must find ways to organize performance-based information and simplify exploration so that the design process is more manageable, while ensuring that performance feedback leads to better outcomes. This paper proposes two new applications of traditional optimization methods that can help simplify early-stage architectural or structural parametric design. The first involves analyzing the design variables considered in the problem, ranking their importance, and determining which ones should be eliminated or emphasized during exploration. The second method clusters designs into families and enables designers to cycle through these families during exploration. Two structural design case studies are presented to illustrate the possibilities created by variable analysis and clustering in conceptual, performance-based design.

-

Valentina Sumini and team win First Place in Mars City Design 2017 Competition for Urban Design2017-10-19, Tags: computation fabrication Mars city computational-design

Valentina Sumini and team win First Place in Mars City Design 2017 Competition for Urban Design2017-10-19, Tags: computation fabrication Mars city computational-designTogether with an interdisciplinary team of MIT students, Valentina Sumini was awarded First Place in a design competition for a future city on Mars. The winning design concept, called Redwood Forest, incorporates inflated biospheres and tree structures anchored into the ground with a root-system-like network of tunnels. For more information, see this article from Slice of MIT and this one from MIT News.

-

Renaud Danhaive presents at the 104th ACSA Annual Meeting in Seattle2016-03-18, Tags: collaboration computation conceptual-structural-design computational-design

Renaud Danhaive presents at the 104th ACSA Annual Meeting in Seattle2016-03-18, Tags: collaboration computation conceptual-structural-design computational-designIn a session titled Structure as Design Knowledge, Renaud presents a paper that connects the history of computation in architecture and structural engineering to current and future digital developments.

-

4.450: Computational Structural Design and OptimizationClass, 2015 - Present

4.450: Computational Structural Design and OptimizationClass, 2015 - PresentThis research seminar focuses on contemporary applications of computation for creative, early-stage structural design and optimization for architecture. Topics covered include computational design fundamentals, including problem parameterization and formulation; design space exploration strategies, including interactive, heuristic, and gradient-based optimization; and computational structural analysis methods, including the finite element method, graphic statics, and approximation techniques. A range of historical and contemporary examples of structural optimization in theory and practice are introduced and investigated as case studies. Students will also complete semester-long individual research projects, which will focus on the development, implementation, or application of an innovative computational approach for structural design. Project images by Juney Lee, Chikara Inamura, Mike Stern, and Geoff Tsai.