Tag: conference

-

A Platform of Design Strategies for the Optimization of Concrete Floor Systems in IndiaMohamed Ismail and Caitlin Mueller, International Conference on Structures and Architecture, 2019

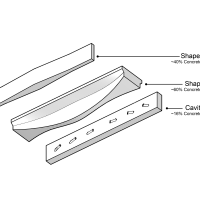

A Platform of Design Strategies for the Optimization of Concrete Floor Systems in IndiaMohamed Ismail and Caitlin Mueller, International Conference on Structures and Architecture, 2019This paper presents a developing platform of design strategies for concrete construction in India. More specifically, this paper will discuss three strategies for the design of horizontal spanning concrete elements. Each strategy involves a different method of structural optimization with varying performance levels based on material reduction and structural capacity. Designed for India’s affordable housing construction, the elements are constrained by the fabrication methods and materials available to India’s construction industry, merging structural design with the development of affordable housing technology. Material savings range from 16% to 50% depending on the strategy. The strategies are used to design, fabricate, and structurally test prototypes, exploring their potential for India’s construction needs.

-

Computational Structural Design and Fabrication of Hollow-Core Concrete BeamsMohamed Ismail, Caitlin Mueller, IASS Symposium 2018: Creativity in Structural Design, 2018

Computational Structural Design and Fabrication of Hollow-Core Concrete BeamsMohamed Ismail, Caitlin Mueller, IASS Symposium 2018: Creativity in Structural Design, 2018The paper presents the results of the design method for a simply supported cavity beam, along with fabrication and load testing results. An optimization algorithm determines the location and rotation of empty plastic water bottles within a prismatic reinforced concrete beam in order to reduce material usage without reducing strength. Designed for India’s affordable housing construction, the beam is constrained by the fabrication methods and materials available to India’s construction industry. This is an effort to merge structural design tools with the development of affordable housing technology, potentially reducing the economic and environmental cost of construction through material efficiency. The designed beam results in a theoretical concrete volume reduction of 16%. Two cavity beams are designed and constructed, and then load-tested in comparison to two solid beams with the same dimensions.

-

Collaborations transcend scales: In conversation with Professor Lorna Gibson2018-10-10, Author: Demi Fang

Collaborations transcend scales: In conversation with Professor Lorna Gibson2018-10-10, Author: Demi FangProfessor Lorna Gibson graduated in Civil Engineering from the University of Toronto and obtained her Ph.D. from the University of Cambridge. She was an Assistant Professor in Civil Engineering at the University of British Columbia for two years before moving to MIT, where she is currently the Matoula S. Salapatas Professor of Materials Science and Engineering. Her research interests focus on the mechanics of materials with a cellular structure such as engineering honeycombs and foams, natural materials such as wood, leaves and bamboo and medical materials such as trabecular bone and tissue engineering scaffolds. She is the co-author of Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties (with MF Ashby) and of Cellular Materials in Nature and Medicine (with MF Ashby and BA Harley).

Recent projects include studies of balsa as a model for bioinspired design of engineering materials and structural bamboo products, analogous to wood products such as oriented strand board. She teaches two subjects: Mechanical Behavior of Materials and Cellular Solids: Structure, Properties and Applications; both are also offered online through edX.

Gibson is a MacVicar Faculty Fellow, MIT’s top award for undergraduate teaching. She has served as Chair of the Gender Equity Committee in the School of Engineering, Chair of the Faculty, and Associate Provost at MIT.

Professor Lorna Gibson gives a keynote at IASS 2018, hosted at MIT.Demi Fang: The theme of the conference is “Creativity in Structural Design.” How do you interpret this theme? What does it bring to mind?

Lorna Gibson: I’ve looked at a lot of natural materials. I look at how they behave mechanically and see what their natural mechanisms of deformation and failure are, and then to try to see what we can learn from those materials for engineering design. This bio-inspired design approach is one we share with a lot of other people.

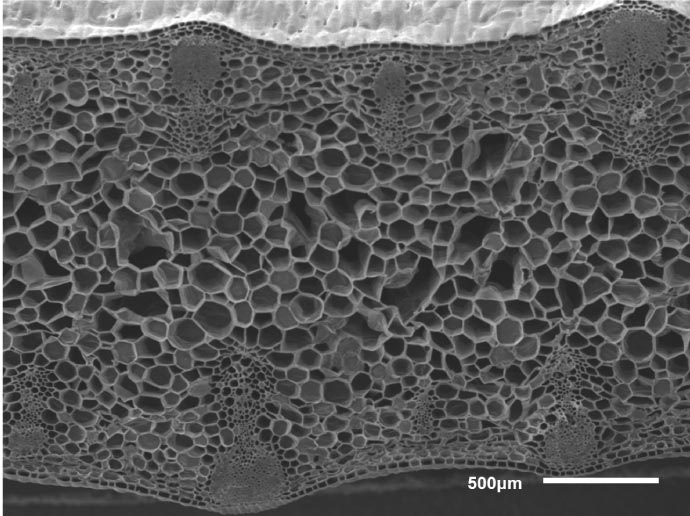

Cellular structures in plants: cross-section of an iris leaf. (Microscopy: Don Galler)DF: What methods do you use to fuel creativity? In what ways do you blend the technical and creative aspects of your work?

LG: I think creativity often arises from doing interdisciplinary things. You become an expert in one field, but then you look at other fields and see they have different ways of doing things: they look at problems differently, or they have different kinds of problems. The way you approach things in a different field makes you rethink in your own field. I think having interdisciplinary research and having people collaborate from different fields is one way that people can be creative.

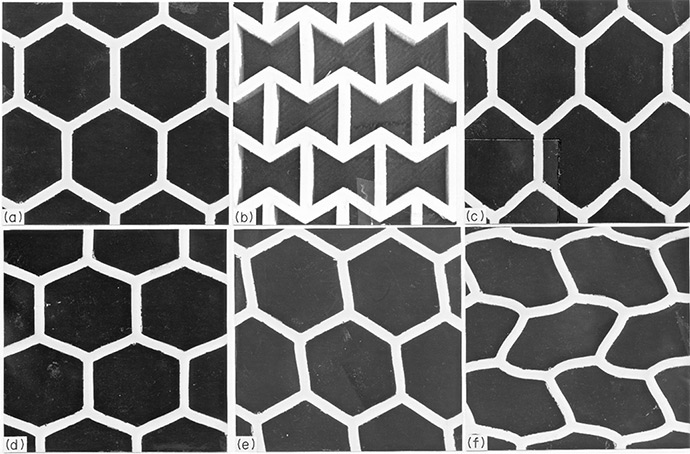

Engineering honeycombs and foams: elastomeric polymers, undeformed (a, b) and deformed in-plane (c-f). L. J. Gibson and M. F. Ashby, Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2 edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.DF: Describe the collaborations in your work.

LG: In our bamboo project, we collaborated with architects in Cambridge and with a wood scientist at the University of British Columbia. The architects were interested in large-scale members, thinking about how the members would be used in actual design and building codes. The wood scientist was interested in the processing of the bamboo; he had worked on the processing of wood composites like oriented strand board (OSB), the particle board, so he took what he knew about processing wood and applied it to the bamboo. Our contribution from MIT was looking at the material science of the bamboo—modeling the microstructure and the mechanical properties of the material. The nice thing about the project was that it went from looking at the microscopic structure of the bamboo, to looking at how you could process the bamboo, to looking at how you would actually use it in a building. It’s too difficult for a single person to span all those different areas of expertise, but by collaborating, we were able to do that.

Bamboo oriented strand board, fabricated by Dr. Greg Smith’s group at University of British Columbia.DF: What are are some pressing, interesting technical challenges that you anticipate in the future in your field?

LG: My field is cellular materials—porous materials like honeycombs and foams. There’s a lot of interest right now in lattice materials, these three-dimensional truss materials, and in how to optimize these materials, optimize their structure, optimize the material you make them from, make them at smaller length scales... I think there’s still a lot of work that remains to be done in that area. There’s also a lot of interest in natural cellular materials—we worked on bamboo, but there’s also trabecular bone, wood, and plant structures. Some of these have very complex structures and I think people will continue working on them.

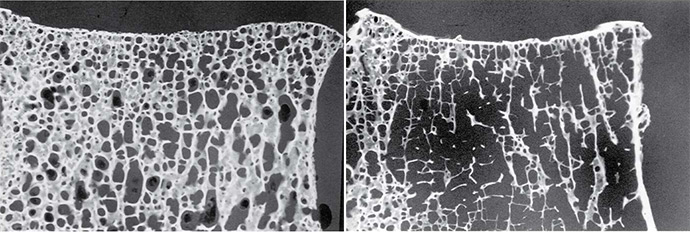

Trabecular bone is porous bone found at the ends of long bones and within the vertebrae, skull, and pelvis. Micrograph of cross-sections of lumbar vertebrae of a 55-year-old woman (left) and an 86-year-old woman (right). S. Vajjhala, A. M. Kraynik, and L. J. Gibson, “A cellular solid model for modulus reduction due to resorption of trabeculae in bone,” J Biomech Eng, vol. 122, no. 5, pp. 511–515, Oct. 2000.DF: Describe the impact of your work outside of academia.

LG: I’ve written several books on cellular solids and they’ve been quite widely used in industry. Outside of my research, I also worked a lot on equity issues for women here at MIT. Each of MIT’s five schools had a committee to help report on the status of women faculty at MIT; I chaired the committee in the school of Engineering. [These efforts resulted in the 2002 Reports of the Committees on the Status of Women Faculty.] I think the collective impact of all of those efforts really had a lot of effect at a lot of places, both in academia and in government and in industry. At the time, it got a tremendous amount of press. The president of MIT, Chuck Vest, had admitted that MIT had discriminated against women faculty, and he and his administration were willing to do things to change MIT. I think that got a lot of attention in lots of places.

Is it perfect now? No, but when I look at what things were like when I was a student – not here, but in Toronto – back then, and what it was like when I came to MIT, and what it’s like now at MIT, it’s totally different.

DF: What advice would you give to your past self or to today’s students?

LG: When I was a graduate student [at the University of Cambridge], my adviser Mike Ashby had been interested in developing this project on cellular solids. He had had a couple of undergraduate students do a senior thesis project on it, but he couldn’t get any graduate students to work on it; nobody wanted to do it with him because it wasn’t a hot, trendy topic at the time (e.g. fracture mechanics, composites). I wasn’t thinking necessarily about becoming a professor and wasn’t worried too much about what I was going to do with it; it just seemed like a really interesting project. My background was in civil engineering, and the topic was like structures but on a tiny length scale.

I worked on it because I thought it was a really interesting project. My thinking was that I’ll learn a lot, and whatever I learn I can apply to the next thing. I never really anticipated I would spend decades after that working on cellular solids! So you don’t always have to do the hot, trendy topic; it’s okay – almost better – to do what’s not hot and trendy because then you can make a big impact developing something new.

DF: What is something you are currently working on that excites you?

LG: I’ve been particularly involved with online teaching on MITx [MIT’s free online courses on edX]. We made a series of videos on how woodpeckers avoid brain injury as part of MITx, and I’d like to make some more videos like that.

Still from Gibson’s “Built to Peck: How Woodpeckers Avoid Brain Injury” MITx series, 2016.DF: How did you get into studying birds?

LG: I’m an amateur bird-watcher, but I like natural history and I like nature. When I was a student, somebody visited our lab and said that woodpeckers had a special cellular material that protected their brains from injury, and that’s how I got interested in the woodpecking thing. There is no such material in their heads. But then I got curious about what was going on instead.

This interview originally appeared in the proceedings for IASS 2018 at which the interviewee was a keynote speaker. These interviews make their first appearance online in this co-published series between this blog and the Form Finding Lab blog with the aim of inspiring a broader audience with the thoughts and insights of these outstanding individuals. Stay tuned on both blogs for more!

More in the series: Neri Oxman | Janet Echelman | Tomohiro Tachi

-

The Arc Lamp workshop at AAG 2018: active bending and digital fabrication

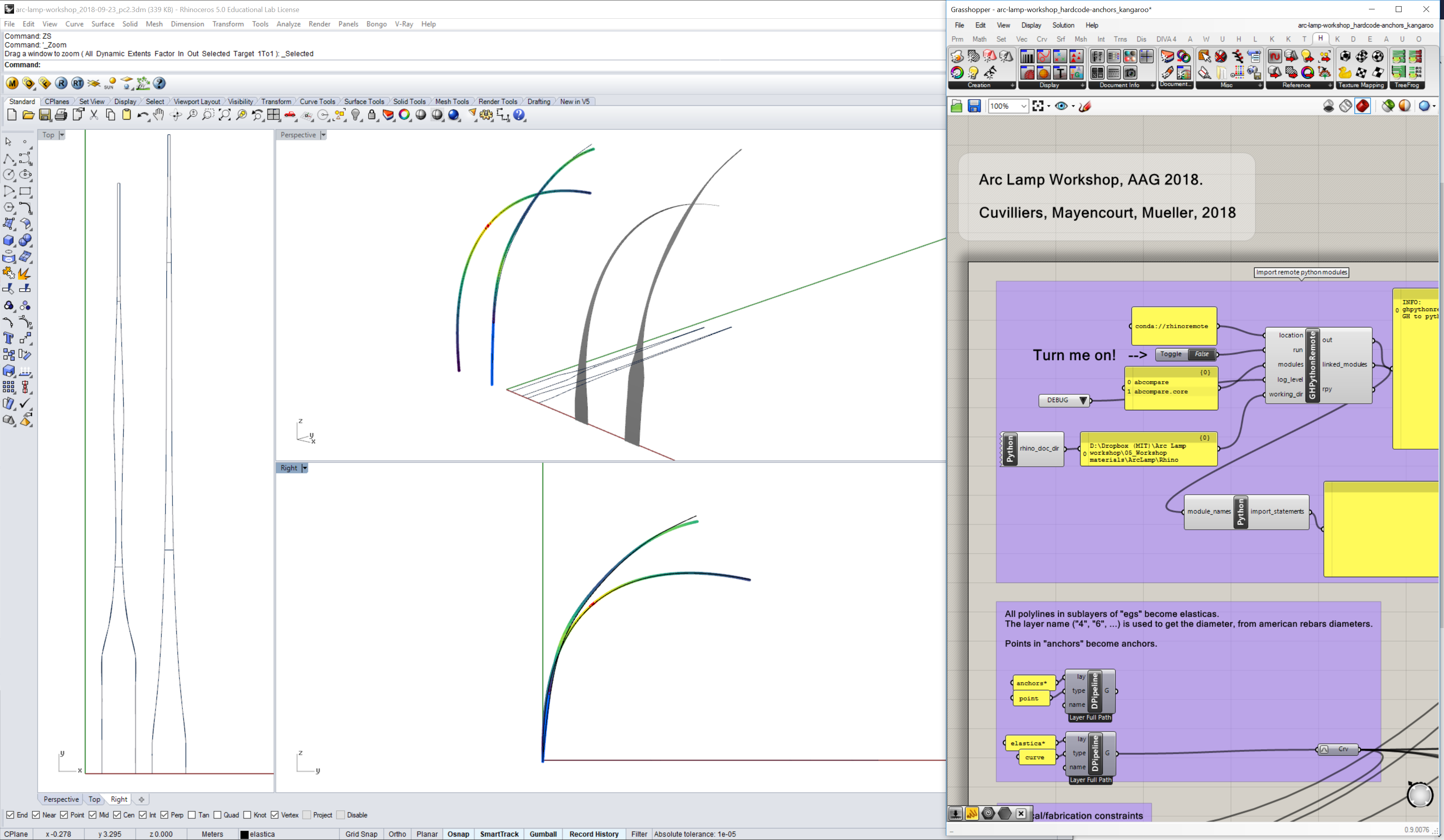

The Arc Lamp workshop at AAG 2018: active bending and digital fabricationDigital Structures' Caitlin Mueller, Paul Mayencourt and Pierre Cuvilliers were in Gothenburg, Sweden this September 2018, teaching a workshop on active bending at the Advances in Architectural Geometry conference hosted at Chalmers University. In this workshop, we explored the design of bending-active structures with variable cross-sections to fit a target design shape. Over the two days, the participants used computational form-finding tools for bending-active structures, and each designed and built an arc lamp. The participants learned state-of-the-art methods for simulating bending-active behavior and for the control and optimization of their equilibrium shapes. These methods could be applied to the design of large-scale bending-active structures such as elastic gridshells.

After a short introductory lecture on active bending structures, the workshop immediately got very practical, with the participants testing the plywood we would use to build the lamps, determining stiffness and resistance. With these values on hand, it was time to start trying out the design workflow on small-scale prototypes. Small teams formed, first design ideas emerged, and we started comparing the designs against their simulated shapes and against each other. The prototypes were laser-cut sheets of plywood, with rudimentary attachments; this made iterating on designs a lot easier.

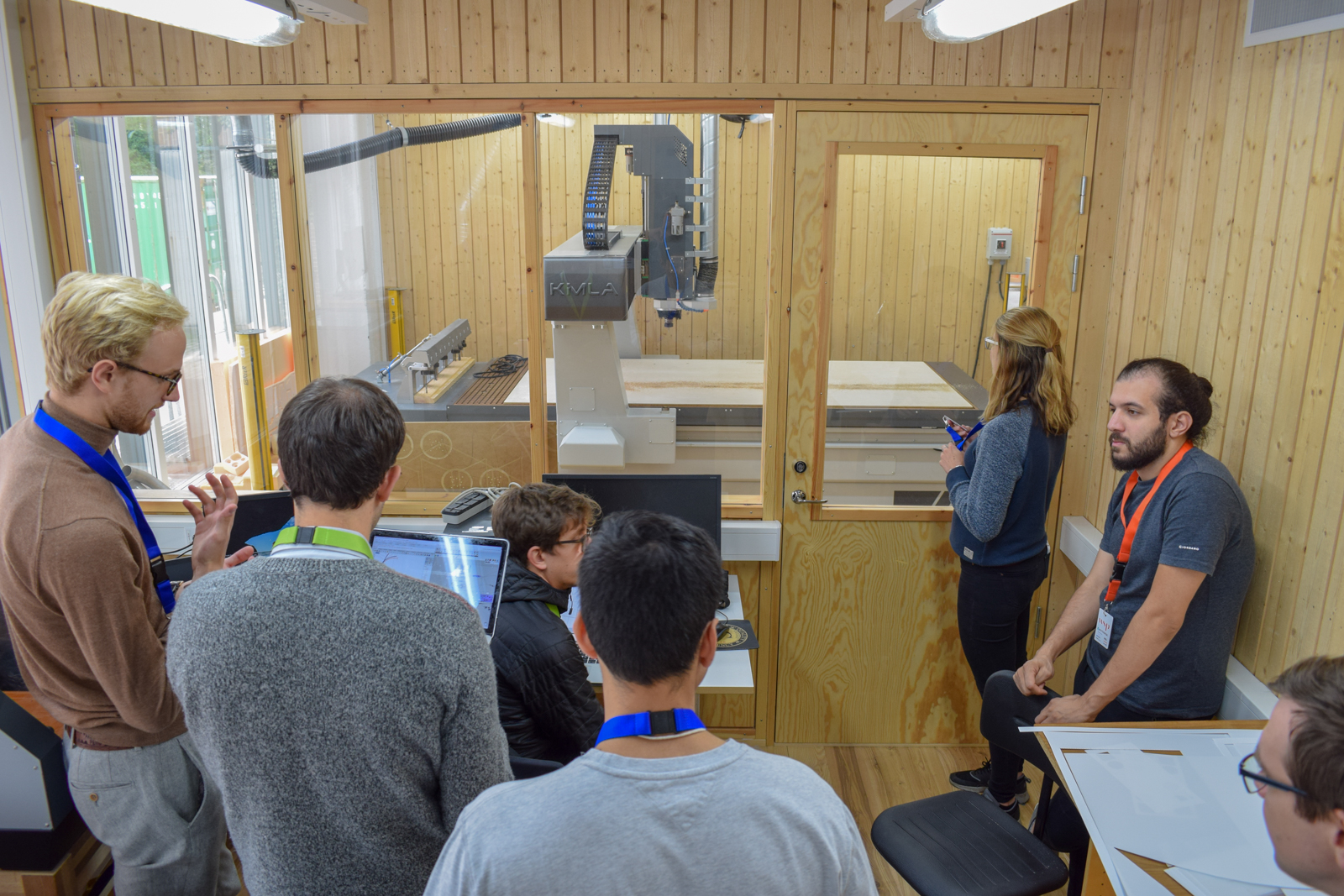

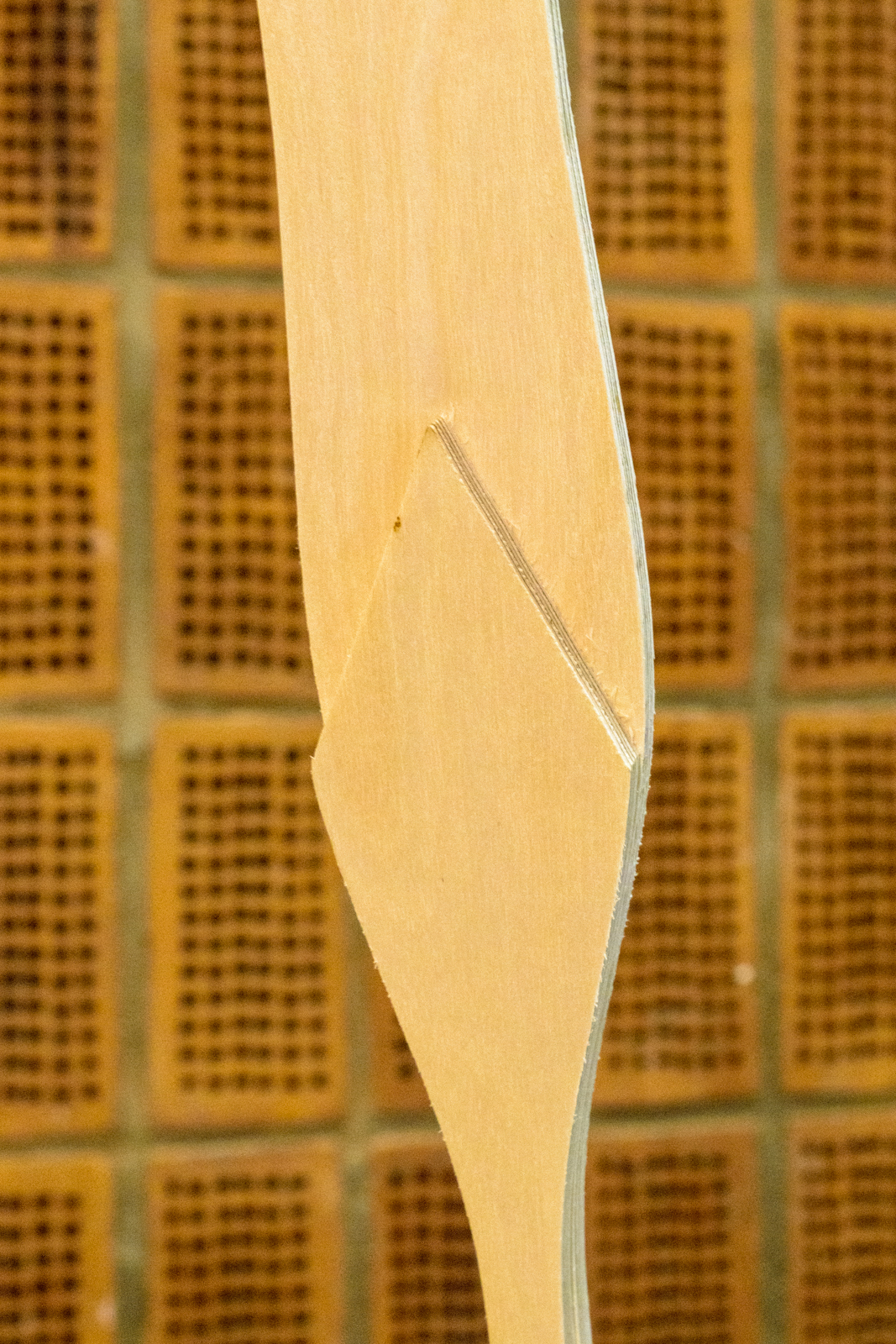

This prototyping stage gave everyone a better sense of the design space we were exploring, and let us start exploring the limits of the software tools. For the next step, we designed lamps at a much larger scale: 2-to-4-meter strips of plywood, from 4-mm- and 6-mm-thick sheets. After finalizing the designs, it was time to start up the CNC router.

As soon as the cuts were ready, it was assembly time. We fabricated bases for the lamps in the beautiful wood workshop of Chalmers University, then moved to the conference space where the lamps would stay on display for 3 days.

Most lamps found their spot next to another bending-active structure, a wooden pavillion designed by Alexander Sehlström.

The rest was spread around the conference space, and all were very intriguing.

Some construction details:

All the lamps we built:

Overall, a great workshop. We all learned a lot in these two days!

-

"Collaboration takes risk and vulnerability": In conversation with artist Janet Echelman2018-09-24, Author: Demi Fang

"Collaboration takes risk and vulnerability": In conversation with artist Janet Echelman2018-09-24, Author: Demi FangJanet Echelman sculpts at the scale of buildings. Her work defies categorization, intersecting Sculpture, Architecture, Urban Design, Material Science, Structural & Aeronautical Engineering, and Computer Science. Echelman’s art transforms with wind and light, and shifts from being “an object you look at, into an experience you can get lost in”.

Her TED talk “Taking Imagination Seriously” has been translated into 35 languages with more than two million views. Oprah ranked Echelman’s work #1 on her List of 50 Things That Make You Say Wow!, and she received the Smithsonian American Ingenuity Award in Visual Arts, honoring “the greatest innovators in America today.” Recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship, Harvard Loeb Fellowship, Aspen Institute Henry Crown Fellowship, and Fulbright Sr. Lectureship, Echelman was named an Architectural Digest Innovator for “changing the very essence of urban spaces.”

Echelman’s educational path has been nonlinear. After graduating from Harvard College, she lived in a Balinese village for 5 years, then completed separate graduate programs in Painting and in Psychology. Recipient of an honorary Doctorate from Tufts University, Echelman most recently served as Visiting Professor at MIT.

Using unlikely materials from fishnet to atomized water particles, Echelman combines ancient craft with computational design software to create artworks that have become focal points for urban life on five continents, from Singapore, Sydney, Shanghai, and Santiago, to Beijing, Boston, New York and London. Permanent commissions can be visited in Porto (Portugal), Richmond (Canada), San Francisco, West Hollywood, Phoenix, Greensboro, Eugene, and Seattle (USA).

Echelman giving her keynote at IASS 2018 at MIT.Demi Fang: What is something you are currently working on that excites you?

Janet Echelman: I’m thinking about creating sculptures that people can physically enter and experience in a more intimate way. I want to bring that idea to the structural advances in my newest permanent installation, Dream Catcher on the Sunset Strip in California, which is the first work to utilize multiple structural levels and combines both tensioned and draped forms moving in between those levels. I’m also working on a commission from the German government for Beethoven2020, to give visual form to the composer’s work in a way that’s relevant today to a broader audience.

Dream Catcher, 2018, West Hollywood, CA, USA (permanent) (110’ W x 100’ H). Colorful sculptural elements combining tensioned and draped form float between four structural layers suspended between two hotel towers on the Sunset Strip. Inspired by the mapping of brain-wave activity during deep REM sleep.DF: The theme of the IASS 2018 conference is “Creativity in Structural Design.” How do you interpret this theme? What does it bring to mind?

JE: When I began my career I was focused on expression through hand-work. I didn’t have any reason to think about "structural design." The first few times I attached temporary sculptures to buildings, we had structural failures, even with the modest loads involved. For my first permanent work at scale, I had to start learning about structure, engineering, documentation, permits, budgets, timelines — all requirements of permanent structures. Since then, my collaborations with structural engineers and computer scientists have become meaningful to my art-making process. The good news is that structural design is both fascinating and enjoyable; I find it can be as much of an outlet for creativity as the “fine arts.” The bad news is it’s really hard. Now, I often work at the intersection of art and structural design, moving fluidly back and forth. My approach has evolved from structural engineering as a requirement to structural concepts as an integral part of the evolution of the art itself.

DF: Describe the collaborations in your work. What do you think makes for successful collaborations?

JE: For me, a collaboration means that we’re seeking an outcome that none of us can predict, and that takes risk and a kind of vulnerability. I describe my work as a “team sport.” Some of my close collaborations with structural engineers and computer scientists have had a profound influence on the direction of my work (David Feldman, Peter Heppel, Clayton Binkley, Alessandro Beghini, Bill Baker, Caitlin Mueller, Jeff Kowalski, Peter Boyer, to name a few key collaborators).

I also collaborate daily within my studio with a tight-knit group of architects and artists; with independent architecture, landscape, and lighting designers; and with our fabricators, ranging from artisans who hand-knot carpets and cut precious stones in India, to American industrial workers who braid, loom, and splice our sculpture.

Dance Collaboration, Stuttgart Ballet, 2014, Stuttgart, Germany (variable size, approx. 30’ W x 30’ H). The artwork becomes an extension of the dancer’s body. As the music score intensifies, the dancer’s gestures match it and the sculpture echoes the movements in a fluid, mesmeric performance.DF: In what ways do you blend the technical and creative aspects of your work?

JE: During my first attempt to collaborate with an engineer, he kept asking, “Whaddya want lady?” and I realized that I needed to understand what is possible first. Now, I approach technical questions with open-ended curiosity, and work with engineers who want to explore what is possible together. I see both old technologies (braiding rope, hand-knotting net) and new technologies (soft-body modeling and analysis) as a fertile ground for art. In addition to pre-industrial and post-industrial methods, I’m also looking at ways to adapt old industrial machines, like looms.

DF: What methods do you use to fuel creativity? How do you work?

JE: I travel and drink in the world as inspiration. I look at the forms of our planet in macro and micro scale, to the patterns of life within it, to the measurement of time, weather patterns, or the paths created by fluid dynamics. When I’m exploring ideas, sometimes I sketch with both hands simultaneously and my eyes closed, putting a brush or pen in both my dominant and nondominant hands. I also do gesture drawings of inanimate objects and site conditions to understand the implied movement within a space.

1.26 Denver, 2010, Denver, CO, USA (130’ L x 140’ W x 135’ H). Echelman’s commission for the Biennial of the Americas. Inspired by environmental data sets of complex, interconnected cycles of the ocean and the rotation of the earth. The earth’s day was shortened by 1.26 microseconds as a result of an earthquake and tsunami.DF: What are currently the most pressing, interesting technical challenges that you tackle in your work, at present or in the future?

JE: Technical constraints have pushed my creativity. I design art to withstand typhoon winds, ice, and snow loads. I try to approach this structural challenge as a feature rather than a bug. In creating permanent work in climates with extreme weather conditions, I find that forms that are able to gracefully adapt to changing circumstances are the most successful, which has led me to design fluidly moving fiber structures. The immense weight of steel armature pushed us to search for the most minimal, elegant structural solutions - including a fiber more than 15 times stronger than steel - and fibers that are 100% impervious to UV from the sun’s rays, high temperatures, pollution, and even chemical reactions - all while remaining soft and fluidly moving.

DF: Describe the impact of your work.

JE: I sometimes observe my work like a fly on the wall and I frequently see total strangers talking to each other about it. In Boston, I watched a man in a business suit lay down in the grass for a minute, quietly staring up at the sculpture billowing in the wind - before he got up to head to his meeting. The Instagram community gives me insight into the impact of the work in their own words. In Washington D.C., a woman posted an image of herself with her child and the comment “Melting with art, as we become part of the exhibition.” My work is mostly seen by city dwellers, but that’s the majority of people on our planet. My sculptures have been installed in cities on five continents, from Singapore, Sydney, Shanghai, and Santiago, to Beijing, Boston, New York and London. I often experience cities as hard-edged and rigid – mostly concrete, steel and glass laid out in straight lines. My art is a counterpoint of softness to all that.

Every Beating Second, 2011, SFO Airport T2, San Francisco, CA, USA (permanent) (177’ L x 84’ W x 29’ H). The SFO Airport asked Echelman to create a “zone of recomposure” past security for their newest terminal; Echelman cut three holes in the roof from which soft forms emerge with color evoking the psychedelic music and beat poets of San Francisco.DF: Who inspires you and your work?

JE: At the moment: Antoni Gaudi’s string models; Gordon Matta Clark and Robert Smithson’s site works; sculptors Eva Hesse and Alexander Calder; painters Giorgio Morandi, Mark Rothko, and Richard Diebenkorn; and Robert Rauschenberg and Trisha Brown’s performances.

DF: What advice would you give to your past self or to today’s students?

JE: Public recognition of my art has only come recently and I never counted on it. My advice to students is to pick a tradition which fascinates you, something you enjoy so much that you won’t mind practicing for a very long time even if public praise never comes. I also think we censor our vision and our dreams too much, and I still have to remind myself frequently to quiet the voice of the internal critic and avoid making compromises too soon.

This interview originally appeared in the proceedings for IASS 2018 at which the interviewee was a keynote speaker. These interviews make their first appearance online in this co-published series between this blog and the Form Finding Lab blog with the aim of inspiring a broader audience with the thoughts and insights of these outstanding individuals. Stay tuned on both blogs for more!

More in the series: Neri Oxman | Tomohiro Tachi

-

IASS 2018 at MIT2018-08-16, Authors: Demi Fang Caitlin Mueller

IASS 2018 at MIT2018-08-16, Authors: Demi Fang Caitlin MuellerWe had a great time last month hosting the 2018 International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures at our home on MIT campus! Caitlin Mueller was the Chair of the Organizing Committee for IASS 2018, joined by John Ochsendorf of MIT, Sigrid Adriaenssens of Princeton University, Bill Baker of SOM, and John Abel of Cornell University.

Much of the conference took place in Eero Saarinen’s iconic Kresge Auditorium.

Throughout the conference we enjoyed outstanding speeches from our plenary speakers. Stay tuned for our next blog posts featuring some of the interviews with our plenary speakers that we published in our abstract book.

Plenary speaker Janet Echelman, artist and principal of Studio Janet Echelman.

Plenary speaker John Ochsendorf of MIT and American Academy in Rome.

Plenary speaker Tomohiro Tachi, associate professor in graphic and computer sciences at the University of Tokyo.

Plenary speaker James O’Callaghan of Eckersley O’Callaghan.

Plenary speaker Chuck Hoberman of Hoberman Associates.56 technical sessions took place throughout the week, where 450 papers were presented.

We also introduced two new events to IASS: a panel on women in design and engineering, and a young designer’s mentorship lunch. These were made possible by Thornton Tomasetti and SOM, respectively.

The panel on women in design and engineering was moderated by Maria Garlock, professor in civil and environmental engineering at Princeton University.

Panelists included Mariana Ibanez of I-K Studio and MIT (podium), Alloy Kemp of Thornton Tomasetti (third from right on stage), Lucile Walgenwitz of Guy Nordenson and Associates (second from right on stage), and Jane Wernick of engineersHRW (far right on stage).

Attendees of the panel were asked to submit and vote on questions to ask the panelists via a live portal.

At the Young Designers’ Mentorship Lunch, conference attendees enjoyed interfacing with peers and mentors at randomly assigned tables over lunch.

Another new feature of the conference was our video competition, which featured 21 fantastic submissions. Check them out!

The Young Designers’ Reception sponsored by Guy Nordenson and Associates took place on the 6th floor of the MIT Media Lab. Attendees enjoyed dinner with views of the Boston skyline and live music performed by Digital Structures’s Demi Fang on the violin.

Photos by Irina ChernyakovaThe conference ended with an evening cruise on the Boston Harbor.

Photos by Olivia HuangNot pictured are the workshops that kicked off the conference and the technical tours that were given throughout the New England area.

We had a great team of volunteers that made sure things went smoothly, in uniform… (photos by Danniely Alexandra and Courtney Stephen)

… and a final shoutout to Danniely Staback who made many aspects of the conference possible and successful!

IASS 2018 would not have been made possible without the support of our sponsors. Thank you!

Photos by Julia Irwin unless otherwise noted. Stay tuned on IASS 2018’s Facebook page for more photos.

-

Paul Mayencourt presents at 2018 International Mass Timber Conference2018-03-21, Tags: conference digital-manufacturing optimization structural-optimization timber fabrication

Paul Mayencourt presents at 2018 International Mass Timber Conference2018-03-21, Tags: conference digital-manufacturing optimization structural-optimization timber fabricationPaul Mayencourt is presenting his work on "Digital Fabrication and Structural Optimization of Timber Beams" at the 2018 International Mass Timber Conference in Portland, Oregon on March 21, 2018. Demi Fang will also be attending the conference to represent Digital Structures.

-

Digital Structures attends IASS 2017 in Hamburg2017-09-30, Authors: Nathan Brown Paul Mayencourt

Digital Structures attends IASS 2017 in Hamburg2017-09-30, Authors: Nathan Brown Paul MayencourtMembers of the Digital Structures research group recently participated in the 2017 Symposium of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures in Hamburg, Germany. This conference brought together researchers from all over the world interested in topics such as digital design technology, shell and membrane structures, deployable structures, and conceptual structural design.

From MIT, Nathan Brown first presented his research on how to use data analysis techniques to automate and simplify early-stage, performance-based design spaces. Next, in a session about inflatable structures, Prof. Caitlin Mueller gave a talk about her research with Valentina Sumini into formfinding for deep space habitats, which could eventually be used to house communities on the Moon or Mars. Finally, after patiently waiting until the last day of the conference, Paul Mayencourt presented his recent work on shape optimization of timber beams, which has the potential to reduce weight and environmental impact in what is perhaps the most commonly used structural member (although columns may have a thing or two to say about that).

The conference also gave Digital Structure members the opportunity to visit historic and contemporary structures in both Hamburg and Berlin. Highlights in Hamburg included the Philharmonie, a glass roof for the central bus station, and a tour of the Hamburg Grossmarkt, a historical concrete roof from 1962, which was organized by the conference. These tours, which often involved a crowd of people exiting a seemingly non-descript, 50-year-old concrete subway station, and then turning around and dodging traffic while trying to get a good picture, must have been curious sight to the locals.

The Philharmonie (left) and interior of the Hamburg Grossmarkt (right)

Berlin also contains many interesting buildings and structures to visit, such as the Sony Center roof, the House of World Cultures, the renovated Olympic Stadium, and the dome on top of the Reichstag building. It also offered the opportunity to visit in person the East Side Gallery, which was the site of a recent Digital Structures bridge design competition submission. As a result of an utter lack of planning, climbing the Reichstag dome was only possible due to a fortuitous, last minute visitation slot opening up at the perfect time. German security must have sensed two young, bright-eyed structural designers who would jump on the opportunity.

Sony Center roof (left) and glass dome of the Reichstag building (right)

Digital Structures members also spent much of the symposium gaining inspiration for how to best organize IASS 2018, which will be held in Boston next July. We are looking forward to hosting next year’s symposium at MIT, and welcome all who are interested in these topics to submit papers and consider participating in the workshops, talks, and other events that will take place next year!