Tag: timber

-

PlumaDesign, 2020

PlumaDesign, 2020With a design framework applicable to any site in the world, the Pluma installation envisions a lightweight future where structures generate more energy than they embody. Earned honorable mention at the IASS 2020 Design Competition.

Pluma demonstrates how form can follow function across disciplines and performance metrics. The design features photovoltaic membranes suspended in a lightweight cable system, resembling a flock of birds in flight.

The shape and orientation of the membrane ensemble is precisely tuned by an optimization algorithm to maximize solar radiation exposure and power generation on the site in Surrey.

Its supporting frame consists of standard timber elements assembled into cruciform sections, with simple, repeated connection details that are cost-effective. The foundation is a concrete slab hollowed out with compressed sawdust blocks as lost formwork, reducing the embodied energy compared to a typical slab by half.

-

INFRAME: Art in elastic timber frameDesign, 2019

INFRAME: Art in elastic timber frameDesign, 2019The INFRAME pavilion is a temporary timber elastic gridshell structure built on the MIT campus in September 2019 as part of Judyta Cichocka's CEE MEng thesis. The structure transforms the function of the public staircase between buildings E15 and E25 on the MIT campus into a performance area. A single layer gridshell becomes a real temporary outdoor stage for electronic music performances, a canvas for a video-mapping show, and has multiple imaginary roles invented by potential next owners. The ultimate goal of the project was to design an elastic timber gridshell, which can be constructed in real-life scenario, providing a functional space for experimental artistic performances and which endeavors to embody the principles of structural art: economy, efficiency and elegance. The challenge lied in development of the design strategy, which allows rapid construction by a small group of inexperienced builders at minimum cost while complying to the building code in Massachusetts (which was required by MIT).

-

Rotational stiffness in timber joinery connections: analytical and experimental characterizations of the Nuki jointDemi L. Fang, Jan Brütting, Julieta Moradei, Corentin Fivet, Caitlin T. Mueller, 4th International Conference on Structures and Architecture, 2019 (Abstract accepted)

Rotational stiffness in timber joinery connections: analytical and experimental characterizations of the Nuki jointDemi L. Fang, Jan Brütting, Julieta Moradei, Corentin Fivet, Caitlin T. Mueller, 4th International Conference on Structures and Architecture, 2019 (Abstract accepted)Historic timber structures feature timber joinery connections that use interlocking geometries rather than fasteners. While timber construction since has gradually favored metallic fasteners, the longevity of historic timber structures utilizing joinery connections demonstrates their feasibility in structural systems and potential to enable sustainable constructions. Advancements in digital fabrication imply the ability to revitalize these complex geometries in competition with conventional fasteners. However, characterization of the mechanical behavior of joinery connections remains to be calibrated across analytical, experimental, and numerical models, let alone systematized across different geometric variations. This research examines the calibration between analytical models and experimental tests for the Nuki joint, a simple beam-through-mortised-column joinery connection. This paper shows that general elastoplastic behavior matches between models, and the analytical model can be calibrated to predict initial stiffnesses within 20% of those determined experimentally. Mismatches between models reveal challenges in calibrating across models: material irregularity of wood and fabrication tolerances.

-

Structural Optimization of Cross-Laminated Timber PanelsPaul Mayencourt, Irina Rasid, and Caitlin Mueller, IASS 2018 Symposium, 2018

Structural Optimization of Cross-Laminated Timber PanelsPaul Mayencourt, Irina Rasid, and Caitlin Mueller, IASS 2018 Symposium, 2018Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) panels are gaining considerable attention in the United States as designers focus on building more ecological and sustainable cities. These panels can speed up construction on site due to their high degree of prefabrication, and consequently, CLT is deployed for slab systems, walls and composite systems in modern buildings. However, the structural use of the material is inefficient in CLT panels. The core of the material does not contribute to the structural behavior and acts merely as a spacer between the outer layers. This project offers an alternative design of an optimized CLT panel with the goal of reducing material consumption and increasing the efficiency of this building component, which can help it become more ubiquitous in building construction.

In this paper, a theoretical model for the behavior of optimized CLT panels is developed, and this model is compared with scaled physical load tests. The results demonstrate that the theoretical model accurately predicts physical behavior. Furthermore, around 20 % of material can be saved without major change in the structural behavior. The reduced material consumption and cost of the proposed optimized CLT panels can help mitigate the ecological impact of the construction industry, while offering a new competitive building product to the market. -

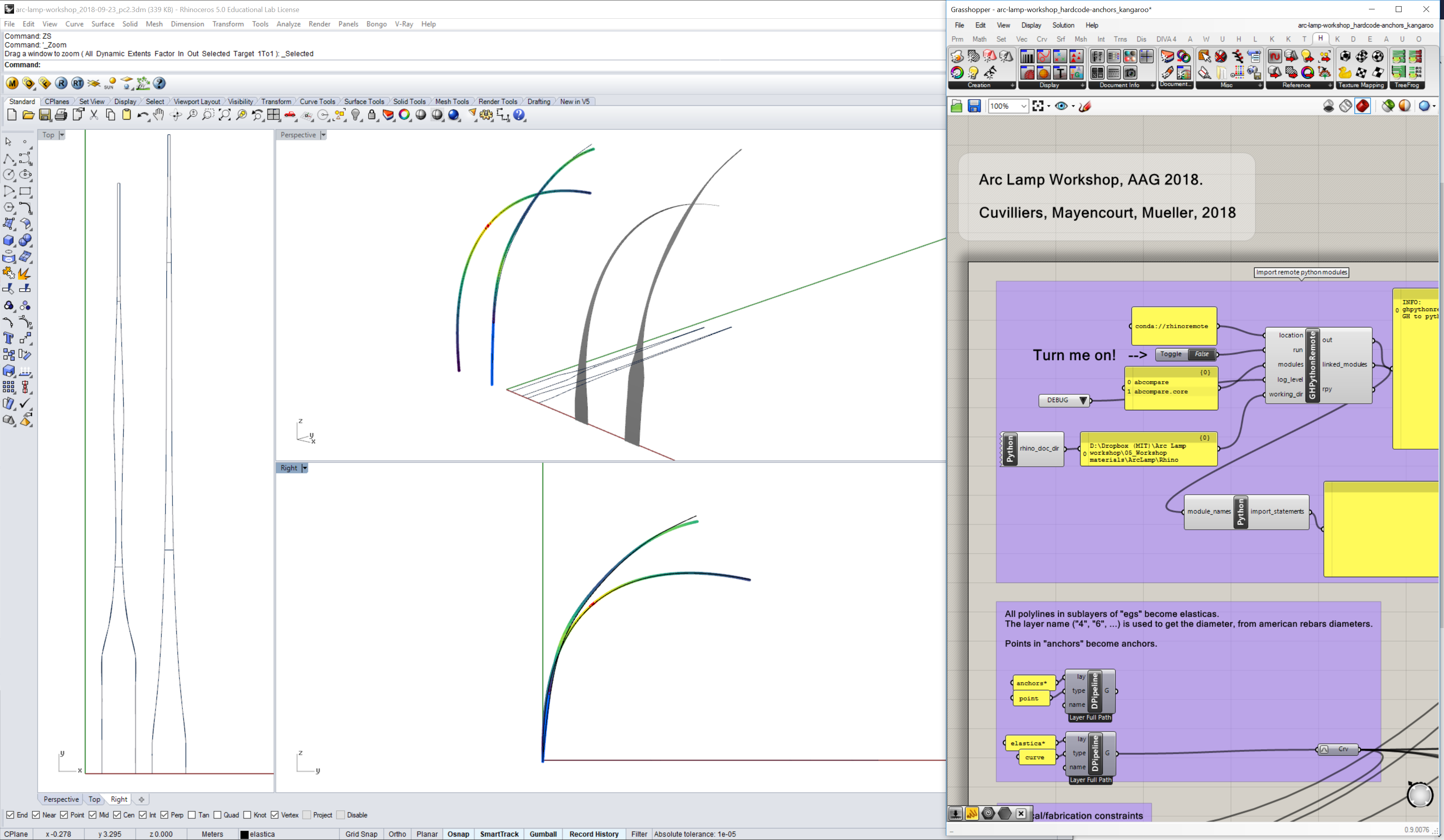

The Arc Lamp workshop at AAG 2018: active bending and digital fabrication

The Arc Lamp workshop at AAG 2018: active bending and digital fabricationDigital Structures' Caitlin Mueller, Paul Mayencourt and Pierre Cuvilliers were in Gothenburg, Sweden this September 2018, teaching a workshop on active bending at the Advances in Architectural Geometry conference hosted at Chalmers University. In this workshop, we explored the design of bending-active structures with variable cross-sections to fit a target design shape. Over the two days, the participants used computational form-finding tools for bending-active structures, and each designed and built an arc lamp. The participants learned state-of-the-art methods for simulating bending-active behavior and for the control and optimization of their equilibrium shapes. These methods could be applied to the design of large-scale bending-active structures such as elastic gridshells.

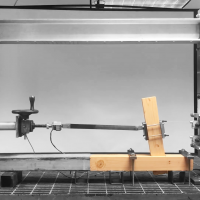

After a short introductory lecture on active bending structures, the workshop immediately got very practical, with the participants testing the plywood we would use to build the lamps, determining stiffness and resistance. With these values on hand, it was time to start trying out the design workflow on small-scale prototypes. Small teams formed, first design ideas emerged, and we started comparing the designs against their simulated shapes and against each other. The prototypes were laser-cut sheets of plywood, with rudimentary attachments; this made iterating on designs a lot easier.

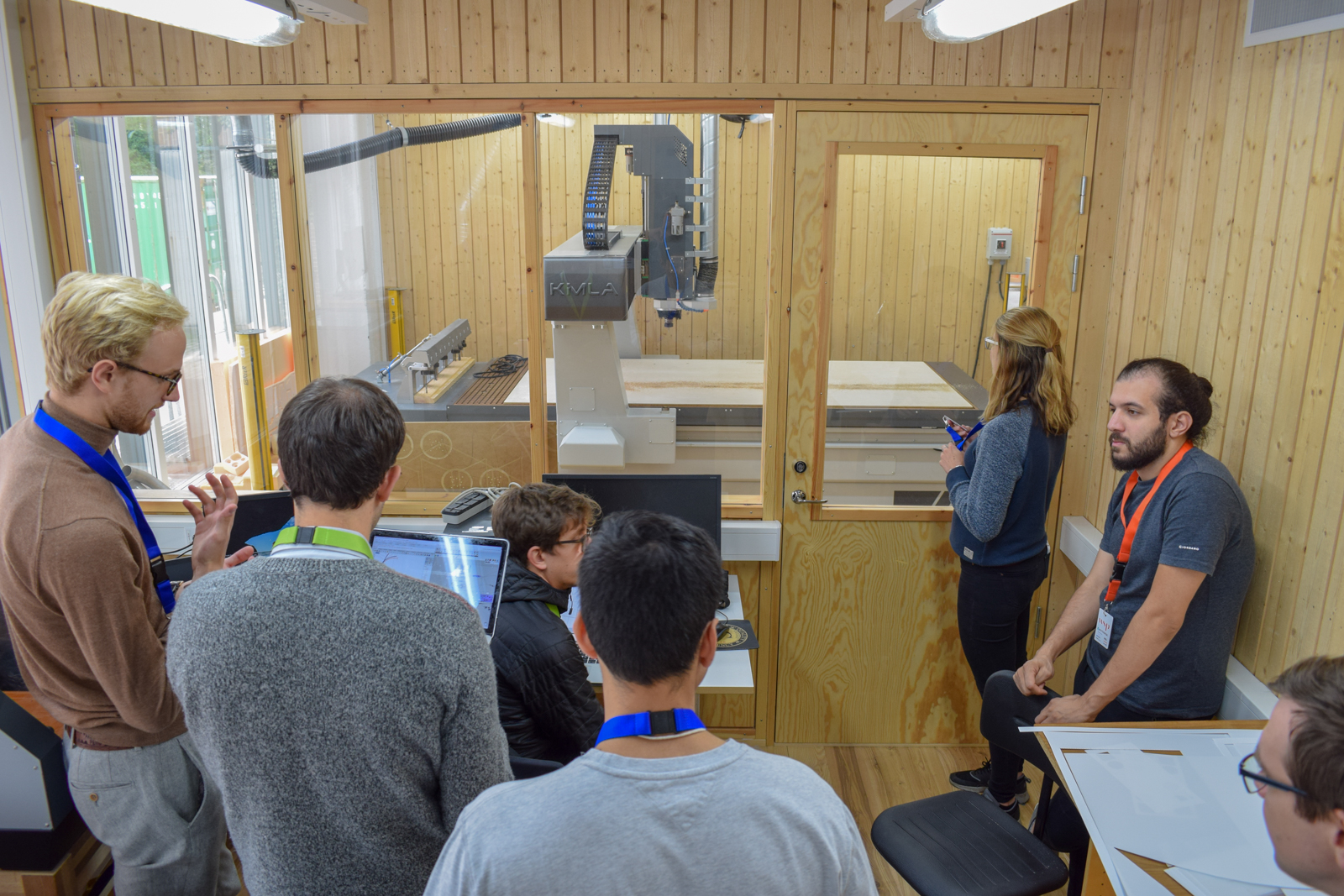

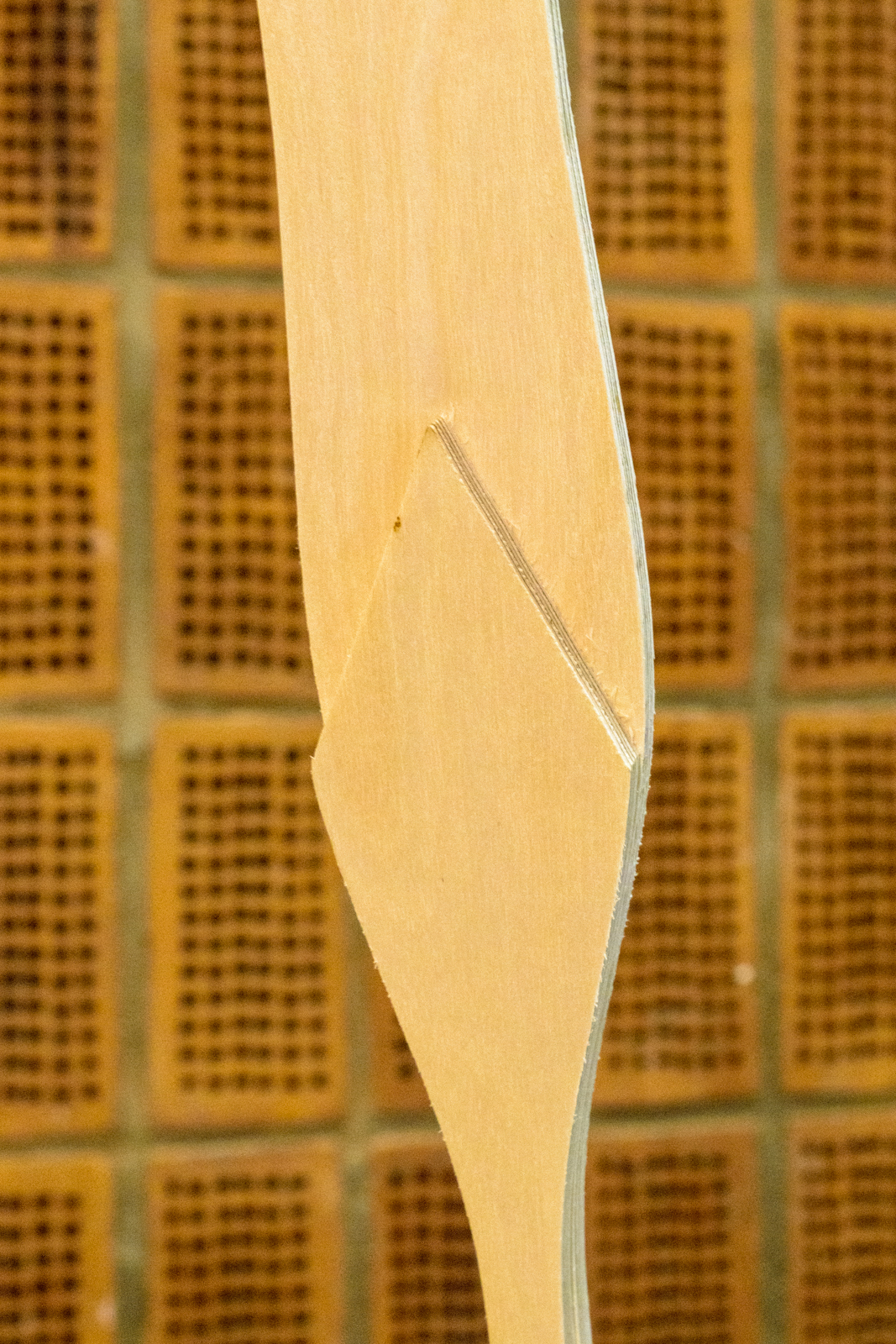

This prototyping stage gave everyone a better sense of the design space we were exploring, and let us start exploring the limits of the software tools. For the next step, we designed lamps at a much larger scale: 2-to-4-meter strips of plywood, from 4-mm- and 6-mm-thick sheets. After finalizing the designs, it was time to start up the CNC router.

As soon as the cuts were ready, it was assembly time. We fabricated bases for the lamps in the beautiful wood workshop of Chalmers University, then moved to the conference space where the lamps would stay on display for 3 days.

Most lamps found their spot next to another bending-active structure, a wooden pavillion designed by Alexander Sehlström.

The rest was spread around the conference space, and all were very intriguing.

Some construction details:

All the lamps we built:

Overall, a great workshop. We all learned a lot in these two days!

-

Integrated design for greenhouse in Portola ValleyDesign, 2018 - Present

Integrated design for greenhouse in Portola ValleyDesign, 2018 - PresentThis ongoing design project looks at an "eco-modernist" custom greenhouse to be built in Portola Valley, California. The objective of this greenhouse is to meet requirements for extended-season plant growth while requiring limited intervention for operation and applying approaches of structural efficiency. Tools such as our Design Space Explorer suite are used to explore and select among a wide design space that meet performance objectives to varying degrees. Local materials and custom structural joinery will be used in the greenhouse construction.

-

Paul Mayencourt embarks on month-long research trip to Japan2018-08-01, Tags: timber

Paul Mayencourt embarks on month-long research trip to Japan2018-08-01, Tags: timberPaul Mayencourt is spending the month of August in Japan for a research fellowship with the Japanese Association for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). His travels will include study and documentation of wood structures, architecture ,and furniture. For a glimpse into his trip, check out his Instagram.

-

Joinery connections in timber frames: analytical and experimental explorations of structural behaviorDemi Fang and Caitlin Mueller, International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS), 2018

Joinery connections in timber frames: analytical and experimental explorations of structural behaviorDemi Fang and Caitlin Mueller, International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS), 2018Innovations in mass timber have ushered in a resurgence of timber construction. Historic timber structures feature joinery connections which geometrically interlock, rarely featuring in modern construction which utilizes steel fasteners for connection details. Research in the geometric potential and mechanical performance of joinery connections remain disparate. This study seeks to develop a performance-driven design framework for the geometry of joinery connections. Experimental and analytical models for three types of joinery connections are presented and compared. The T* type joint, which uses a T-shaped tenon instead of a dovetail, experimentally showed the highest rotational stiffness. The analytically predicted rotational stiffness of the T* type joint comes within 20% of the experimentally determined value. A preliminary parametric study through the analytical model demonstrates how geometric parameters can be varied to achieve desired rotational stiffness.

-

Paul Mayencourt presents at 2018 International Mass Timber Conference2018-03-21, Tags: conference digital-manufacturing optimization structural-optimization timber fabrication

Paul Mayencourt presents at 2018 International Mass Timber Conference2018-03-21, Tags: conference digital-manufacturing optimization structural-optimization timber fabricationPaul Mayencourt is presenting his work on "Digital Fabrication and Structural Optimization of Timber Beams" at the 2018 International Mass Timber Conference in Portland, Oregon on March 21, 2018. Demi Fang will also be attending the conference to represent Digital Structures.

-

Design, mechanics, and optimization of interlocking wood jointsResearch, 2017 - Present

Design, mechanics, and optimization of interlocking wood jointsResearch, 2017 - PresentDespite the longstanding craft of interlocking wood joints in North American and East Asian carpentry, modern timber structures frequently use metal connectors in mid-rise construction. This research explores the structural capabilities of interlocking joints between beams and columns for mid-rise timber frame construction. Research methods include parametric design, structural modelling, digital fabrication, and experimental load testing.

-

Computational tools and experimental making in timber construction: In conversation with Christopher Robeller2017-11-03, Authors: Demi Fang Paul Mayencourt

Computational tools and experimental making in timber construction: In conversation with Christopher Robeller2017-11-03, Authors: Demi Fang Paul MayencourtOf the many exciting innovations in digital fabrication permeating architecture research today, the work of Christopher Robeller stands out in the growing field of timber construction. Robeller completed his PhD in 2015 on the integral mechanical attachment of timber panels at Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL)’s laboratory for timber construction, IBOIS. He spent the following two years as a post-doctoral researcher at the Swiss National Centre in Research (NCCR), applying his research to the construction of a fully functioning building: the Vidy Theatre. Recently appointed Junior Professor in Digital Timber Construction at TU Kaiserslautern, Robeller presented his process and experience working on the Vidy at the ACADIA 2017 conference at MIT in early November of this year.

Robeller also stopped by to chat with us about his work and his thoughts on wood, the built environment, and the importance of experimentation in making. The questions and responses below have been edited for clarity.

Digital Structures: How did you get to be interested in and involved with wood?

Christopher Robeller: My family has been working with timber for a couple of generations, but for more pragmatic things like making windows. My fascination from childhood was always that wood was a nice material to work with - it’s not too dirty, and it’s something you can craft. It’s even got a nice smell to it! It’s a material I’m very passionate about.

DS: Can you describe your training in architecture and/or engineering?

CR: I studied architecture at the London Metropolitan University. It was not a mixed course, but I was always very interested in engineering at the same time. I was very impressed by all of the creativity and ideas being generated in architecture school, but there was a point where I realized that in order to make it really work, you have to overcome a lot of engineering challenges, and only if you really manage that can you make really great architecture.

I have combined my interests in architecture and engineering in the last few years. I first worked with Achim Menges, through which I collaborated a bit with Jan Knippers’s laboratory, a team of mostly engineers. When I went to IBOIS at EPFL for my PhD, I found that I was one of the few architects - there were times when I was one of two architects on a ten-person team.

It would be a shame for a building to have a strong and interesting architectural concept but have details that don’t match the quality of the rest of the building. I found an opportunity through the PhD to focus on those more in-depth aspects of geometry, fabrication, and engineering.

DS: What are your thoughts on relationship between architecture and engineering?

CR: In my traditional experience in architecture, there is not much interaction. You expect the engineer to figure it out, and most projects rely on the state-of-the-art. Architects and engineers get to work much more closely together in more experimental projects in academia.

Computational tools offer a chance for architects and engineers to work together. These tools offer control over design, and that control is valuable in both fields. There is only so much you can do with a software that comes off the shelf that was developed for certain purpose; if you want to use the software for a different purpose, you have to modify the software to make it do what you want it to do. Architects and engineers are starting to take advantage of this.

This area is where the two fields reach a bit of a common language. I am seeing computer scientists, civil engineers, and architects work on similar collaborative models. You might find a very interesting solution for your architectural or engineering problem in some algorithm that has just been developed by some computer scientists. Then you can get together and plug in together if you’re working on a common ground such as a common programming language.

DS: What are your thoughts on the relationship between academia and practice?

CR: They can be worlds apart, especially in timber construction. The community of timber construction is highly skilled but can sometimes be rather conservative. On the other hand, there is the creative and artistic community of architects who design amazing things with timber. It’s really interesting how you have to find a balance between these two groups because they can be very far from each other.

Given the complexity of wood, you have to bring the two groups together. You have to talk to the companies in the construction industry that specialize in timber. In design and engineering, we are usually generalists working with many materials, whereas these companies have long ago specialized in one material and have gained a lot of knowledge over the decades. That’s something that should be respected. If you get in touch with them - which you only do through these experimental projects - you learn a lot from them.

There is a lot of discussion right now over the social component of digitalization. There is a danger of neglecting people who are not in the loop. Once again, computational tools allow you to integrate people in industry into the design process. I think we’ve done that with the Vidy Theatre: we went to companies, talked to the experts there, and included them in the process. I specifically developed a program that the fabricator there could use. We didn’t use software that eliminate the engineer and the fabricator from the design and manufacturing process. It’s something we should think about: how these digital workflows can incorporate specialists.

DS: Do you hope to continue bridging these fields - architecture and engineering, and research and practice - through your new professorship?

CR: I am definitely trying to bring the four worlds together. People in practice already know how to do things; they’re absolute professionals in the state-of-the-art. In teaching, the beauty is in not having that expertise yet. This lets you think about things in a completely different way, in a free and open way, and you might come up with interesting and intuitive solutions.

For example, I was making the first prototype for a timber plate shell construction project in the workshop by myself, with my hands. I was assembling the prototype on its side because intuitively it made sense to allow the weight of the elements to help with insertion. But in building design, it was being designed right-side-up as usual, and that was what was causing all the problems when we tried to put together a larger prototype. It wasn’t until we finally thought back to the first prototype that I built sideways that we realized what the problem was. I might not have had that experience if I hadn’t made that prototype myself.

Timber plate shell prototype assembled on its side. Image courtesy of Christopher Robeller.

Great architects and engineers are people who quite often have been working physically themselves making things, making prototypes and models. This very rarely happens in actual architecture-engineering design processes - it’s only in academia that a designer of a building actually goes and makes not only a representational model but a functional model of some joint or assembly - himself.

Robeller (left) chats with DS students Courtney Stephen (middle) and Paul Mayencourt (right).

DS: What is something that excites you the most about future possibilities in wood?

CR: We can do amazing things with timber in fabrication, and I think that’s the biggest development in the last ten, twenty years. If you had shown me our work on the Vidy Theatre ten years ago, I would have thought it was magic. Now having done all of it, it doesn’t really seem like magic anymore.

We have come a far way, and it’s much easier to do these things now. While geometry processing and fabrication have become more manageable, the building implementations allow us to focus on new challenges such as integrated concepts for structural engineering and building physics.

One reason I went to IBOIS is because of their machinery (5-axis CNC machine). If you want to experiment with the making of today, you need the technology to be accessible; you don’t have that everywhere. In educational institutions, it’s very important to not only have the technology but to have it accessible to the greater community.

It’s funny, I talked to companies like Blumer Lehmann - they had their first 5-axis machine in 1985. That’s how long they’ve had it! Mechanically, not much has changed. You probably could have done the Vidy Theatre back then. The computer was surely capable enough. The limitation was accessibility: you didn’t have the CNC machinery in universities, at least in architecture and engineering. CNC technology may have been developed at MIT, but it took a long time for it to come into architecture and building in a way that’s accessible to the architecture research community.

Construction of Vidy Theatre. Image courtesy of Christopher Robeller.

Another exciting challenge I see is that not only do we have something very beautiful, but we also have something that can make a positive impact in terms of the ecological construction that we need so much. It’s like having your cake and eating it too! We have something beautiful, something interesting, we can address the challenges of digitalization by making jobs more pleasant and more interesting and less hard manual work, and at the same time we can maybe make it more ecologic. But that’s really a maybe; I’m very self-critical about my work so far, and it has not been something focusing on sustainability - yet. But this is clearly something I see as a realistic possibility and something I want to look more into.

DS: Do you have any advice for young researchers and architects who are interested in exploring and applying timber innovations?

CR: Be passionate and be creative. When you first begin as a student, you’re very free from any state-of-the-art that tells you how things are supposed to work. You have to use the moment. Eventually, of course, you have to learn all of the things, but every stage of the journey is an interesting step.

-

Computational Structural Optimization and Digital Fabrication of Timber BeamsResearch, 2016 - Present

Computational Structural Optimization and Digital Fabrication of Timber BeamsResearch, 2016 - PresentStructural optimization techniques offer means to design efficient structures and reduce their impact on the environment by saving material quantities. However, until very recently, the resulting geometrical complexity of an optimized structural design was costly and difficult to build. Today, fabrication processes such as 3D printing and Computer Numeric Control (CNC) machining in the construction industry reduces the complexity to produce complex shapes.

This research aims to combine computational structural optimization and digital fabrication tools to create a new timber architecture. A key opportunity for material savings in buildings lies in ubiquitous structural components in bending, especially in beams. This research explores old and new techniques for shaping structural timber beams.

-

Computational Structural Optimization and Digital Fabrication of Timber BeamsPaul Mayencourt, Joaquin S. Giraldo, Eric Wong, and Caitlin Mueller, Proceedings of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) Symposium, 2017

Computational Structural Optimization and Digital Fabrication of Timber BeamsPaul Mayencourt, Joaquin S. Giraldo, Eric Wong, and Caitlin Mueller, Proceedings of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures (IASS) Symposium, 2017This paper focuses on optimizing beams made of solid timber sections through a CNC subtractive milling process. An optimization algorithm shapes beams and reduces the material quantities by up to 50% of their initial weight. A series of these beams are then fabricated and load tested, and their strength is compared to standard timber sections.

-

Paul Mayencourt presents at Wood at Work Montreal2017-10-27, Tags: computation fabrication digital-manufacturing embodied-carbon structural-optimization timber

Paul Mayencourt presents at Wood at Work Montreal2017-10-27, Tags: computation fabrication digital-manufacturing embodied-carbon structural-optimization timberPaul Mayencourt presented research on opportunities for using structural optimization and digital fabrication to shape wood structural beams and building components at the third annual Wood at Work conference in Montreal.

-

New Structural Systems in Small-Diameter Round TimberAurimas Bukauskas, MIT BSA Thesis, 2015

New Structural Systems in Small-Diameter Round TimberAurimas Bukauskas, MIT BSA Thesis, 2015Trees, when used as structural elements in their natural, round form, are up to five times stronger than the largest piece of dimensioned lumber they could yield. Additionally, these whole-timbers have a lower effective embodied carbon than any other structural material. When combined into efficient structural configurations and joined using specially-engineered connections, whole- timber has the potential to replace entire steel and concrete structural systems in large-scale buildings, bridges, and infrastructure. Whole-timber may be the most appropriate structural solution for a low-carbon and fully renewable future in both developed temperate regions and the developing Global South. To reduce barriers to adoption, including project complexity and cost, a standardized “kit of parts” in whole-timber is proposed. This thesis proposes new designs for the first and most important element of this kit: a structurally independent column in whole-timber. A 20’ compound column in whole-timber is prototyped at full-scale. New, simple calculation methods are developed for estimating the buckling capacity of tapered timbers. Based on conservative assumptions, the embodied carbon of whole-timber column systems is shown to be between 30% and 70% lower than conventional steel systems.

-

Whole-timber structural systemsResearch, 2014 - 2015

Whole-timber structural systemsResearch, 2014 - 2015Trees, when used as structural elements in their natural, round form, are up to five times stronger than the largest piece of dimensioned lumber they could yield. Additionally, these whole-timbers have a lower effective embodied carbon than any other structural material. When combined into efficient structural configurations and joined using specially-engineered connections, whole-timber has the potential to replace entire steel and concrete structural systems in large-scale buildings, bridges, and infrastructure. Whole-timber may be the most appropriate structural solution for a low-carbon and fully renewable future in both developed temperate regions and the developing Global South. To reduce barriers to adoption, including project complexity and cost, a standardized “kit of parts” in whole-timber is proposed. This project proposes new designs for the first and most important element of this kit: a structurally independent column in whole-timber. A 20’ compound column in whole-timber is prototyped at full-scale. New, simple calculation methods are developed for estimating the buckling capacity of tapered timbers. Based on conservative assumptions, the embodied carbon of whole-timber column systems is shown to be between 30% and 70% lower than conventional steel systems.